Volume 4, Issue 3 (Summer 2015)

J Occup Health Epidemiol 2015, 4(3): 131-138 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Beheshti M, Firoozi Chahak A, Alinaghi Langari A, Poursadeghiyan M. Risk assessment of musculoskeletal disorders by OVAKO Working posture Analysis System OWAS and evaluate the effect of ergonomic training on posture of farmers. J Occup Health Epidemiol 2015; 4 (3) :131-138

URL: http://johe.rums.ac.ir/article-1-146-en.html

URL: http://johe.rums.ac.ir/article-1-146-en.html

Related article in

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

Similar articles

1- Dept. of Occupational Health, Faculty of Health, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

2- Dept. of Occupational Health, Faculty of Health, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran. ,ali_firoozi66@yahoo.com

3- Dept. of Occupational Health, Faculty of Health, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran.

4- Dept. of Ergonomics, School of Rehabilitation, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Dept. of Occupational Health, Faculty of Health, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran. ,

3- Dept. of Occupational Health, Faculty of Health, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran.

4- Dept. of Ergonomics, School of Rehabilitation, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Article history

Received: 2015/01/10

Accepted: 2015/04/6

ePublished: 2015/09/28

Accepted: 2015/04/6

ePublished: 2015/09/28

Subject:

Occupational Health

Full-Text [PDF 618 kb]

(8203 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (12559 Views)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Figure 2: Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in different body parts during 12 months using the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire

Table 4: The relationship between musculoskeletal disorders and demographic variables

.jpg)

Figure 3: Ergonomic risk level of musculoskeletal disorders in a variety of agricultural tasks based on OWAS method

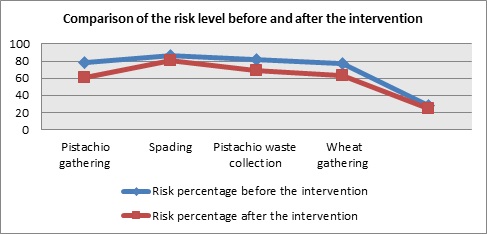

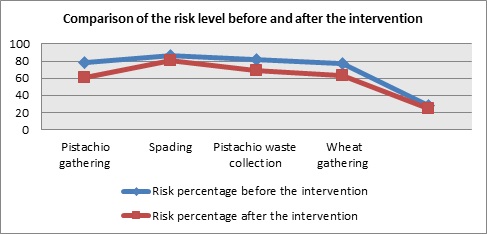

Figure 4: Comparison of the risk level before and after the intervention

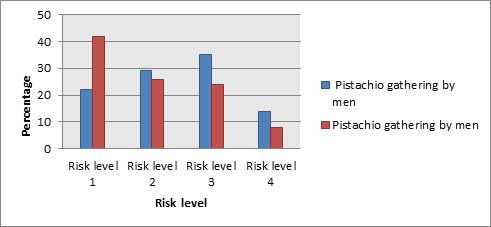

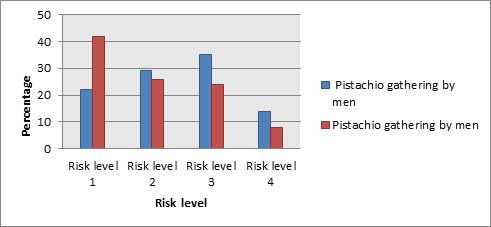

Figure 5: Posture analysis and risk assessment results of men and women in pistachio gathering according to OWAS

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the ergonomic risk of MSDs and investigate the effect of ergonomic interventions and 8 weeks of training on exposure to them. As shown in table 1, pain in the neck, back, waist, hips, knees, and ankles during the 3 months or 12 months of completing the questionnaire increased significantly with increase in work experience (P < 0.050). There was a significant relationship between age and work experience, and the prevalence of MSDs (P ˂ 0.001). Before the intervention, in the pistachio gathering tasks, 78% of working posture was in risk levels 2, 3, and 4. This frequency was reduced to 61% after the intervention. In addition, this reduction was observed in pistachios and wheat gathering tasks. It should be noted that risk levels 1, 2, 3, and 4 are, respectively, natural posture, stressful posture, harmful posture, and very harmful posture.

The results showed that agricultural tasks, due to the nature of the work and hazardous occupational factors, are considered as traumatic tasks; so that during the 12 months of the study, 83.56% of the subjects presented symptoms of MSDs in at least 1 of the 9 studied body parts. Based on the NMQ and report of the studied farmers, MSDs had the highest prevalence in the back and knees. This can be due to poor posture or static activity that is commonly observed in various tasks such as harvesting and pistachios gathering. This means that attention to risk factors related to these areas and their elimination can be an important step in improving the working conditions and the preventing MSDs. Moreover, prevention programs should focus on controlling the risk factors related to these areas. In the study performed by Ismailian et al. in Tehran Tile Factory, the most important problems reported were inappropriate access and working height (18). The results showed that age and work experience have significant relationships with the occurrence of MSDs and this finding is in agreement with other studies (19-21).

In this study, no relationship was found between MSDs, and height and weight. This result also proves the effect of occupational factors on ergonomic injuries (22, 23). The results showed that 25.3% of the subjects had neck pain that was similar to the results of study by Joh Nrosecrance on MSDs in farmers in Kansas, America (24). The results of this study were lower than that of the study by Afifehzadeh-Kashani et al. in surgeons and surgical residents of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran (25). The risk level was higher in wheat gathering and pistachio collecting tasks, in which most of the movement is static, compared to other tasks. Risk level in pistachio and wheat gathering tasks was lowered significantly after the ergonomic interventions and required training compared to before the intervention (P ˂ 0.050). Nevertheless, no significant change was observed in spading and fertilizing tasks. This illustrates that taking corrective measures in these tasks should be prioritized in ergonomics intervention programs. The results of this study showed that 46.4% of subjects experienced pain and discomfort in the knees and this prevalence was lower than that reported by Farhad Ghamari et al. in an ergonomic assessment of bakers in Arak, Iran (26).

Conclusion

The results of this assessment showed that in various agricultural activities, farmers' postures were different and each one had a different ergonomic risk level. It can be concluded that the prevalence of MSDs in agriculture is relatively high. Furthermore, the level of risk that was obtained based on OWAS indicates the presence of traumatic conditions and working environment in this industry. Hence, taking corrective measures to improve working conditions is essential.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to faculty members of the Department of Occupational Health at Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Iran, and all managers and farmers who helped us in this project.

Conflict of interests: None declared.

Full-Text: (496 Views)

Introduction

Human resources are the main survival factor in a system and humans are considered as an integral part of the work environment (1, 2). Individuals are affected by harmful factors in their work environments. Exposure to such factors can be the cause of occupational diseases. Musculoskeletal disorders are one of the most common occupational diseases (3, 4). In 1989, 6500000 cases of diseases and injuries were reported in America and 5 million individuals suffered from musculoskeletal injuries due to inappropriate working conditions (5). Studies have shown that almost 10% of occupational accidents are related to the musculoskeletal system and are caused by sudden movements, lifting, repetitive motions, or overuse of body organs. It is estimated that in Europe 4000000 worker suffer from work-related musculoskeletal disorders* (WMSDs) (more than 30% of workers) and in America 44% of work-related diseases is related to the musculoskeletal system (6). One of the important sectors in production is the agricultural sector. Occupational health and safety are the most important factors that can increase efficiency and productivity in the agricultural sector (7). The agricultural sector has traditionally lacked the required health facilities, but in recent decades it has been greatly changed and the health and safety of farmers have been improved. However, farmers are exposed to many occupational risk factors, one of which is musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in agriculture (8). The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that annually 170,000 farmers die due to their occupation, which is more relevant to work with machines and poisons. This means that the risk of death in farming is twice that of other occupations. A study in America showed that 26% of farmers suffer from back pain, which is related to their occupation (9). MSDs are injuries and diseases of the muscles, tendons, ligaments, joints, nerves, blood vessels, and all structures that are involved in motion. The relationship of these injuries with ergonomic risk factors has been proven. Although these disorders are not often fatal, they result in failure and even permanent disability (9). MSDs are a health-related issue and a major cause of disability worldwide (10-12). In America, MSDs are the cause of loss of working time in more than 600,000 workers (13). WMSDs are more common in the hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, and neck; thus, exposure is studied in these areas of the body (11, 14). There are various ergonomic factors in agricultural occupations including non-standard body positions during work, kneeling, curved spine, pressure and torsion in body organs, loading, maintenance activities, inappropriate load lifting, and lack of rest breaks for long periods of time (15, 16). Postural analysis can be a strong and effective technique for ergonomic assessment of work activities. Through ergonomic assessment of risks arising from inappropriate body positions, the risk of WMSDs can be predicted and strategies can be provided to protect workers and increase productivity. An important method of postural assessment is the OVAKO Working Posture Analysis System (OWAS).

In the OWAS method, working status and stress on the musculoskeletal system are identified and then classified in terms of terminology, requirements, and priorities (8). This method was first developed and introduced in Finland and in a steel production company. It should be noted that the inter observer reliability of this method has been reported as 90% and higher. The comparison of OWAS postural assessment results and SELSPOT system measurement (SELective light SPOT recognition) results shows that OWAS provide correct results about the condition of the body pressure and hence, has acceptable reliability. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of MSDs among farmers using the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (MNQ) and OWAS.

Material and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 400 farmers. Data were collected through interviews and questionnaires. The studied farmers were in rural areas; therefore, after determining the number of villages and providing a list of their villages, 5 villages were selected randomly and, in each village, farmers were randomly selected while working and interviewed. This study conducted using Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (MNQ) and OWAS methods. OWAS is a postural assessment method that is conducted by encoded posture. This method often evaluates the posture of the back (4 postures), arms (3 postures), and legs (7 postures), and displaced load in the form of 3 items (17). In this study, the work phase was specified through occupational analysis, and in every phase, body posture was sampled and the code corresponding to each posture was registered at regular intervals of 30 to 60 seconds during work. Sampling in each work phase lasted 20 to 40 minutes, because each working cycle lasted 20 to 40 minutes. Subsequently, working postures were coded and analyzed. It should be noted that in this study, sampling was performed through photographing postures. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of this study consisted of the willingness to participate in the project, lack of any diseases and MSDs, and at least one year of work experience. In ergonomic assessment of farmers' tasks, 5 major tasks including gathering of pistachios by men, gathering of pistachios by women, spading, gathering of pistachio waste, picking of wheat, and fertilizing were evaluated using OWAS and NMQ. Some examples of the physical conditions of farmers are illustrated in figure 1.

Human resources are the main survival factor in a system and humans are considered as an integral part of the work environment (1, 2). Individuals are affected by harmful factors in their work environments. Exposure to such factors can be the cause of occupational diseases. Musculoskeletal disorders are one of the most common occupational diseases (3, 4). In 1989, 6500000 cases of diseases and injuries were reported in America and 5 million individuals suffered from musculoskeletal injuries due to inappropriate working conditions (5). Studies have shown that almost 10% of occupational accidents are related to the musculoskeletal system and are caused by sudden movements, lifting, repetitive motions, or overuse of body organs. It is estimated that in Europe 4000000 worker suffer from work-related musculoskeletal disorders* (WMSDs) (more than 30% of workers) and in America 44% of work-related diseases is related to the musculoskeletal system (6). One of the important sectors in production is the agricultural sector. Occupational health and safety are the most important factors that can increase efficiency and productivity in the agricultural sector (7). The agricultural sector has traditionally lacked the required health facilities, but in recent decades it has been greatly changed and the health and safety of farmers have been improved. However, farmers are exposed to many occupational risk factors, one of which is musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in agriculture (8). The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that annually 170,000 farmers die due to their occupation, which is more relevant to work with machines and poisons. This means that the risk of death in farming is twice that of other occupations. A study in America showed that 26% of farmers suffer from back pain, which is related to their occupation (9). MSDs are injuries and diseases of the muscles, tendons, ligaments, joints, nerves, blood vessels, and all structures that are involved in motion. The relationship of these injuries with ergonomic risk factors has been proven. Although these disorders are not often fatal, they result in failure and even permanent disability (9). MSDs are a health-related issue and a major cause of disability worldwide (10-12). In America, MSDs are the cause of loss of working time in more than 600,000 workers (13). WMSDs are more common in the hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, and neck; thus, exposure is studied in these areas of the body (11, 14). There are various ergonomic factors in agricultural occupations including non-standard body positions during work, kneeling, curved spine, pressure and torsion in body organs, loading, maintenance activities, inappropriate load lifting, and lack of rest breaks for long periods of time (15, 16). Postural analysis can be a strong and effective technique for ergonomic assessment of work activities. Through ergonomic assessment of risks arising from inappropriate body positions, the risk of WMSDs can be predicted and strategies can be provided to protect workers and increase productivity. An important method of postural assessment is the OVAKO Working Posture Analysis System (OWAS).

In the OWAS method, working status and stress on the musculoskeletal system are identified and then classified in terms of terminology, requirements, and priorities (8). This method was first developed and introduced in Finland and in a steel production company. It should be noted that the inter observer reliability of this method has been reported as 90% and higher. The comparison of OWAS postural assessment results and SELSPOT system measurement (SELective light SPOT recognition) results shows that OWAS provide correct results about the condition of the body pressure and hence, has acceptable reliability. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of MSDs among farmers using the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (MNQ) and OWAS.

Material and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 400 farmers. Data were collected through interviews and questionnaires. The studied farmers were in rural areas; therefore, after determining the number of villages and providing a list of their villages, 5 villages were selected randomly and, in each village, farmers were randomly selected while working and interviewed. This study conducted using Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (MNQ) and OWAS methods. OWAS is a postural assessment method that is conducted by encoded posture. This method often evaluates the posture of the back (4 postures), arms (3 postures), and legs (7 postures), and displaced load in the form of 3 items (17). In this study, the work phase was specified through occupational analysis, and in every phase, body posture was sampled and the code corresponding to each posture was registered at regular intervals of 30 to 60 seconds during work. Sampling in each work phase lasted 20 to 40 minutes, because each working cycle lasted 20 to 40 minutes. Subsequently, working postures were coded and analyzed. It should be noted that in this study, sampling was performed through photographing postures. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of this study consisted of the willingness to participate in the project, lack of any diseases and MSDs, and at least one year of work experience. In ergonomic assessment of farmers' tasks, 5 major tasks including gathering of pistachios by men, gathering of pistachios by women, spading, gathering of pistachio waste, picking of wheat, and fertilizing were evaluated using OWAS and NMQ. Some examples of the physical conditions of farmers are illustrated in figure 1.

.jpg)

Figure 1: Some of the physical conditions of farmer

On the other hand, the NMQ is a useful tool in determining the symptoms of MSDs, which were read and explained to the subjects by the researcher. In this study, to determine the effect of ergonomics principles training on workers posture, training courses were held as lectures, and then, workers’ postures were evaluated.

.jpg)

Figure 2: Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in different body parts during 12 months using the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire

Results

Figure 2 shows the frequency of MSDs in the period of 12 months in different parts of the body. As can be seen in the charts, low back pain and knee problems had the highest frequency. These issues are caused by standing or sitting for a long period of time, displacement and manual material handling, and undesirable workstations. According to figure 2, the highest frequency of MSDs was observed in the waist and knees. Among individuals with work experience of over 20 years, 13% to 67% frequency of pain in these areas was reported, while in subjects with less than 9 years of experience, the frequency of pain in the abovementioned areas varied from 2% to 28% (Table 1).

Figure 2 shows the frequency of MSDs in the period of 12 months in different parts of the body. As can be seen in the charts, low back pain and knee problems had the highest frequency. These issues are caused by standing or sitting for a long period of time, displacement and manual material handling, and undesirable workstations. According to figure 2, the highest frequency of MSDs was observed in the waist and knees. Among individuals with work experience of over 20 years, 13% to 67% frequency of pain in these areas was reported, while in subjects with less than 9 years of experience, the frequency of pain in the abovementioned areas varied from 2% to 28% (Table 1).

Table 1: The relationship between pain in different organs of the body and work experience during 3 months and 12 months before completing the questionnaire

| P-Value | More than 20 years | 20-10 years | Less than 9 years | Body part Work experience |

|||

| Percentage Frequency | Frequency | Percentage Frequency | Frequency | Percentage Frequency | Frequency | ||

| 0.001 | 42 | 42 | 22.7 | 40 | 16.1 | 20 | Neck pain (3 months) |

| 0.001 | 42 | 42 | 22.7 | 40 | 15.3 | 19 | Neck pain (12 months) |

| 0.001 | 24 | 24 | 10.8 | 19 | 6.5 | 8 | Back pain (3 months) |

| 0.001 | 25 | 25 | 10.8 | 19 | 5.6 | 7 | Back pain (12 months) |

| 0.001 | 63 | 63 | 59.1 | 104 | 27.4 | 34 | Back pain (3 m onths) |

| 0.001 | 63 | 63 | 59.7 | 105 | 28.2 | 35 | Pain (12 months) |

| 0.003 | 14 | 14 | 6.3 | 11 | 2.4 | 3 | Hip pain (3 months) |

| 0.007 | 13 | 13 | 6.3 | 11 | 2.4 | 3 | Hip pain (12 months) |

| 0.001 | 67 | 67 | 49.4 | 87 | 26.6 | 33 | Knee pain (3 months) |

| 0.001 | 67 | 67 | 49.4 | 87 | 25.8 | 32 | Knee pain (12 months) |

| 0.005 | 25 | 25 | 17 | 30 | 8.9 | 11 | Ankle pain (3 months) |

| 0.003 | 26 | 26 | 17 | 13 | 8.9 | 11 | Ankle pain (12 months) |

The data presented in table 2 indicate that the frequency of pain in various body parts in individuals with short stature (less than 160 cm) was higher than individuals with height of over 160 cm, but this difference was statistically significant only in the neck and knees (P < 0.050).

Table 2: The relationship between pain in different body parts and height during 3 months and 12 months before completing the questionnaire

| P-Value | More than 170 cm | 160-170 cm | Less than 160 cm | Height Body part |

|||

| Percentage Frequency | Frequency | Percentage Frequency | Frequency | Percentage Frequency | Frequency | ||

| 0.003 | 19.8 | 18 | 20.5 | 36 | 36.1 | 48 | Neck pain (3 months) |

| 0.010 | 19.8 | 18 | 21 | 37 | 34.6 | 46 | Neck pain (12 months) |

| 0.471 | 16.5 | 15 | 11.9 | 21 | 11.3 | 15 | Back pain (3 months) |

| 0.471 | 16.5 | 15 | 11.4 | 20 | 12 | 16 | Back pain (12 months) |

| 0.082 | 44 | 40 | 47.7 | 84 | 57.9 | 77 | Back pain (3 months) |

| 0.098 | 44 | 40 | 48.9 | 86 | 57.9 | 77 | Pain (12 months) |

| 0.307 | 5.5 | 5 | 5.7 | 10 | 9.8 | 13 | Hip pain (3 months) |

| 0.217 | 4.4 | 4 | 5.7 | 10 | 9.8 | 13 | Hip pain (12 months) |

| 0.015 | 48.4 | 44 | 39.2 | 69 | 55.6 | 74 | Knee pain (3 months) |

| 0.016 | 47.3 | 43 | 39.2 | 69 | 55.6 | 74 | Knee pain (12 months) |

| 0.833 | 16.5 | 15 | 17.6 | 31 | 15 | 20 | Ankle pain (3 months) |

| 0.762 | 16.5 | 15 | 18.2 | 32 | 15 | 20 | Ankle pain (12 months) |

Results of chi-square test showed that body weight had no statistically significant correlations with pain in the neck, back, hips, knees, and ankles in the last 3 and 12 months (P > 0.050) (Table 3). The only significant relationship was observed in the back. The relationship between demographic variables and MSDs is provided in table 4. As can be seen, average age and work experience in individuals with MSDs was higher than individuals who did not report symptoms of MSDs.

Table 3: The relationship between pain in different body parts and weight during 3 months and 12 months before completing the questionnaire

| P-Value | More than 70 kg | 59-70 kg | Less than 59 kg | Weight Body part |

|||

| Percentage Frequency | Frequency | Percentage Frequency | Frequency | Percentage Frequency | Frequency | ||

| 0.455 | 21.1 | 16 | 28.2 | 50 | 24.52 | 36 | Neck pain (3 months) |

| 0.424 | 21.1 | 16 | 28.2 | 50 | 23.8 | 35 | Neck pain (12 months) |

| 0.012 | 6.6 | 5 | 10.2 | 18 | 19 | 28 | Back pain (3 months) |

| 0.025 | 6.6 | 5 | 10.7 | 19 | 18.4 | 27 | Back pain (12 months) |

| 0.909 | 48.7 | 37 | 51.4 | 91 | 49.7 | 73 | Back pain (3 months) |

| 0.921 | 48.7 | 37 | 51.4 | 91 | 51 | 75 | Pain (12 months) |

| 0.781 | 6.6 | 5 | 6.2 | 11 | 8.2 | 12 | Hip pain (3 months) |

| 0.901 | 6.6 | 5 | 6.2 | 11 | 7.5 | 11 | Hip pain (12 months) |

| 0.965 | 46.1 | 35 | 46.3 | 82 | 47.6 | 70 | Knee pain (3 months) |

| 0.990 | 46.1 | 35 | 46.3 | 82 | 46.9 | 69 | Knee pain (12 months) |

| 0.868 | 18.4 | 14 | 16.4 | 29 | 15.6 | 23 | Ankle pain (3 months) |

| 0.868 | 18.4 | 14 | 16.9 | 30 | 15.6 | 23 | Ankle pain (12 months) |

Number of observations concerning the tasks of pistachio gathering by men, pistachio gathering by women, spading, gathering of pistachio waste, picking of wheat, and fertilizing were 601, 401, 201, 201, 201, and 101, respectively. Results of posture analysis and risk assessment using OWAS according to task type are shown in figure 3.

Table 4: The relationship between musculoskeletal disorders and demographic variables

| P-Value | Lack of musculoskeletal disorders | Presence of musculoskeletal disorders | Variable | ||

| SD | Mean | SD | Mean | ||

| < 0.001 | 8.6 | 31.42 | 13.7 | 43.76 | Age (years) |

| < 0.872 | 7.8 | 63.75 | 9.5 | 62.65 | Weight (kg) |

| < 0.651 | 7.8 | 163.87 | 8.4 | 165.63 | Height (cm) |

| < 0.001 | 4.3 | 8.8 | 6.5 | 13.8 | Work experience (years) |

.jpg)

Figure 3: Ergonomic risk level of musculoskeletal disorders in a variety of agricultural tasks based on OWAS method

Figure 4: Comparison of the risk level before and after the intervention

Figure 4 shows the total risk level (risk levels 1-4) before and after ergonomic interventions and necessary training in the studied tasks.

As shown in figure 3, the highest percentage of normal posture was allocated to the task of fertilizing (72%), although a harmful or very harmful posture was observed in this task. In wheat gathering, 77% of the body posture observed was harmful and only 23% was normal. Pistachio gathering was the single task performed by women. Posture analysis and risk assessment results of men and women in pistachio gathering according to OWAS are shown in figure 5. In pistachio gathering, women’s postures were better and more natural than men.

As shown in figure 3, the highest percentage of normal posture was allocated to the task of fertilizing (72%), although a harmful or very harmful posture was observed in this task. In wheat gathering, 77% of the body posture observed was harmful and only 23% was normal. Pistachio gathering was the single task performed by women. Posture analysis and risk assessment results of men and women in pistachio gathering according to OWAS are shown in figure 5. In pistachio gathering, women’s postures were better and more natural than men.

Figure 5: Posture analysis and risk assessment results of men and women in pistachio gathering according to OWAS

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the ergonomic risk of MSDs and investigate the effect of ergonomic interventions and 8 weeks of training on exposure to them. As shown in table 1, pain in the neck, back, waist, hips, knees, and ankles during the 3 months or 12 months of completing the questionnaire increased significantly with increase in work experience (P < 0.050). There was a significant relationship between age and work experience, and the prevalence of MSDs (P ˂ 0.001). Before the intervention, in the pistachio gathering tasks, 78% of working posture was in risk levels 2, 3, and 4. This frequency was reduced to 61% after the intervention. In addition, this reduction was observed in pistachios and wheat gathering tasks. It should be noted that risk levels 1, 2, 3, and 4 are, respectively, natural posture, stressful posture, harmful posture, and very harmful posture.

The results showed that agricultural tasks, due to the nature of the work and hazardous occupational factors, are considered as traumatic tasks; so that during the 12 months of the study, 83.56% of the subjects presented symptoms of MSDs in at least 1 of the 9 studied body parts. Based on the NMQ and report of the studied farmers, MSDs had the highest prevalence in the back and knees. This can be due to poor posture or static activity that is commonly observed in various tasks such as harvesting and pistachios gathering. This means that attention to risk factors related to these areas and their elimination can be an important step in improving the working conditions and the preventing MSDs. Moreover, prevention programs should focus on controlling the risk factors related to these areas. In the study performed by Ismailian et al. in Tehran Tile Factory, the most important problems reported were inappropriate access and working height (18). The results showed that age and work experience have significant relationships with the occurrence of MSDs and this finding is in agreement with other studies (19-21).

In this study, no relationship was found between MSDs, and height and weight. This result also proves the effect of occupational factors on ergonomic injuries (22, 23). The results showed that 25.3% of the subjects had neck pain that was similar to the results of study by Joh Nrosecrance on MSDs in farmers in Kansas, America (24). The results of this study were lower than that of the study by Afifehzadeh-Kashani et al. in surgeons and surgical residents of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran (25). The risk level was higher in wheat gathering and pistachio collecting tasks, in which most of the movement is static, compared to other tasks. Risk level in pistachio and wheat gathering tasks was lowered significantly after the ergonomic interventions and required training compared to before the intervention (P ˂ 0.050). Nevertheless, no significant change was observed in spading and fertilizing tasks. This illustrates that taking corrective measures in these tasks should be prioritized in ergonomics intervention programs. The results of this study showed that 46.4% of subjects experienced pain and discomfort in the knees and this prevalence was lower than that reported by Farhad Ghamari et al. in an ergonomic assessment of bakers in Arak, Iran (26).

Conclusion

The results of this assessment showed that in various agricultural activities, farmers' postures were different and each one had a different ergonomic risk level. It can be concluded that the prevalence of MSDs in agriculture is relatively high. Furthermore, the level of risk that was obtained based on OWAS indicates the presence of traumatic conditions and working environment in this industry. Hence, taking corrective measures to improve working conditions is essential.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to faculty members of the Department of Occupational Health at Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Iran, and all managers and farmers who helped us in this project.

Conflict of interests: None declared.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |