Volume 10, Issue 4 (Autumn 2021)

J Occup Health Epidemiol 2021, 10(4): 266-273 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ibikunle M A, Afolabi R F, Bello S. Job Satisfaction and Psychological Distress among Teachers in Selected Schools in Ibadan, Southwestern Nigeria in 2021: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Occup Health Epidemiol 2021; 10 (4) :266-273

URL: http://johe.rums.ac.ir/article-1-500-en.html

URL: http://johe.rums.ac.ir/article-1-500-en.html

Related article in

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

Similar articles

1- MSc in Epidemiology, Dept. of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

2- PhD in Statistics, Dept. of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

3- PhD in Public Health and Epidemiology, Department of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. ,drsegunbello@yahoo.com

2- PhD in Statistics, Dept. of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

3- PhD in Public Health and Epidemiology, Department of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. ,

Article history

Received: 2021/11/22

Accepted: 2021/12/1

ePublished: 2021/12/25

Accepted: 2021/12/1

ePublished: 2021/12/25

Subject:

Occupational Health

Full-Text [PDF 389 kb]

(1336 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3942 Views)

Table 1. Secondary school teachers' demographic profiles in Ibadan

Table 2. Job satisfaction and psychological distress (GHQ scores) among teachers in the selected secondary schools in Ibadan, 2021

Full-Text: (677 Views)

Introduction

Job satisfaction has attracted a lot of attention in the workplace as experts believe that job satisfaction patterns can influence work efficiency, performance, participation, absenteeism, and employee retention, being an indicator of overall individual wellbeing [1]. Various academics have explained job satisfaction in various ways. In a study, job satisfaction was defined as an attitudinal variable resulting from the aggregation and balance of job likes and dislikes [2]. In addition, it was defined as any :union: of physiological, psychological, and environmental factors, leading to positive or negative job satisfaction [3].

Job satisfaction can be influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Accordingly, intrinsic factors are work-related activities primarily observed through classroom activities, such as recognition and promotion activities, whereas extrinsic factors are environmental variables, such as salaries, policies, and practices among others [4]. The importance of job satisfaction cannot be underestimated due to its major links to work performance as well as physical and mental health. This is the reason why dissatisfied teachers are more likely to be absent from work, have higher turnover intentions, and want to leave the teaching profession, thereby lowering student morale and leading to poor academic performance [5]. Furthermore, job satisfaction is directly related to work proficiency among teachers, which increases their enthusiasm for more research in educational fields and improves student academic performance [6].

Workplace success is influenced by good mental health and job satisfaction. Because of the direct relationship between job satisfaction and mental health, if teachers are emotionally fit, they will be more productive at work, leading to higher morale and a healthier lifestyle [7].

A link between work satisfaction and mental health has been established in several studies. Although previous findings indicate that psychological wellbeing is linked to job satisfaction, current findings imply that the link could be reciprocal, with mental health influencing job satisfaction as well [8].

According to research, some predictors of job satisfaction among teachers include salary, heavy workloads, insufficient cooperation among colleagues and administrators, low prestige attached to teaching, duplication of roles, lack of connections between policymakers and teachers, occupational insecurity, and career stagnation [9–12]. Studies show that teachers fall into the category of workers who cope with a variety of work-related stresses, resulting in long-term physical and mental health issues, low productivity, poor work commitment, intentions to quit, and increased burnout levels [13,14]. Similarly, epidemiological reports indicate that teachers have mental health complications at a relatively higher rate than other professions, which may be due to their work stress, pupil-related difficulties, and interpersonal disputes with colleagues [15].

However, in emerging countries like Nigeria, there are insufficient data about psychological health of teachers. Only a number of studies have reported the effect of psychological factors on job satisfaction among secondary school teachers in Nigeria using different General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) assessment instruments [16–19].

According to the literature review, job satisfaction among secondary school teachers in Nigeria ranges from 27.1 to 59.6% [17–19]. Furthermore, a similar study in Ghana found that 51% of the teachers were satisfied and 49% were dissatisfied with their job, having been higher than other studies [20]. These differences show the complexities of job satisfaction and reflect various metrics used for assessing it. The diversity observed in job satisfaction levels among teachers may have been caused by differences in the techniques utilized and cultural features of different teachers. Other studies adopted job satisfaction measures, such as the generic satisfaction scale and single item methods of assessment [17, 19].

In a study in the Benin City among teachers in private secondary schools, 17.2% of the dissatisfied teachers had psychological disorders, while 11.2% of the teachers who were satisfied had psychological disorders with a GHQ score greater than 4 [19]. Using GHQ-12, Okwaraji et al reported that 32.9% of the teachers had psychiatric morbidity in Enugu, Nigeria [17]. In contrast, using GHQ-28, Ofovwe et al reported that 20.8% of the teachers in the Egor local government of the Edo State had a score of 4 or above, which indicated the presence of psychiatric disorders [18]. These variations indicate complexities of psychological health and reflect various scales used to assess psychiatric morbidity. The use of different instruments, varied cutoffs, and sociocultural features of different individuals may contribute to the heterogeneity in psychiatric morbidity among these teachers.

Secondary education serves as a link between primary and tertiary education, being an important part of a child's formative years [21]. Job satisfaction has been recently the focus of discussion among educational psychologists due to the reduced satisfaction levels among secondary school teachers, which has been linked to the declining levels of education in Nigeria. According to some studies, secondary school graduates' intellectual capacity is not different from that of school dropouts [16, 21]. There is a low priority for treating mental health disorders in Nigeria, which has resulted in high levels of depression, anxiety, and depression among teachers; accordingly, it is supposed that teachers do not bother to seek care because of the stigmas and beliefs associated with psychological disorders in Nigeria [22, 23]. Secondary education is a very sensitive stage in both Nigeria and in many developing countries. Besides, teaching in this part of the world is considered a part-time job until better offers or higher-paying jobs become available. Thus, it is important not to neglect teachers and to ensure that their job satisfaction leads to healthy living. Although some studies have been conducted on the level of job satisfaction and the presence of psychological distress among secondary school teachers in Nigeria, few have assessed the relationship between job satisfaction and psychological disorders among secondary school teachers. This fact has resulted in a lack of data on the relationship between job satisfaction and psychological distress among secondary school teachers in southwestern Nigeria. Against this backdrop, this study aims to determine job satisfaction levels and to investigate the link between job satisfaction and psychological distress among teachers in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional research was conducted among secondary school teachers aged 18-67 years in Ibadan from July to August 2021. Ibadan is the capital of the Oyo State with 11 Local Government Areas (LGAs) located in southwestern Nigeria. In addition, it is the largest indigenous city by the geographical area and the third most populous city in Nigeria. The majority of Ibadan residents are Yoruba’s’. The choice of schools reflects the type of secondary schools in the metropolis, which include public and private secondary schools. This study included all teachers who had worked in secondary schools for at least one year, who aged from 18 to 67 years as well as full-time teachers. Teachers ill at the time of the study as well as those who refused to participate were excluded from the study.

The teachers were chosen via multistage random sampling. At stage one, northwestern Ibadan, i.e. (IBNW) LGA, was selected purposively. The IBNW LGA was chosen due to the fact that it is one of the largest LGAs in the Ibadan metropolis and part of the old Ibadan municipality of the Oyo State [24]. At stage two, simple random sampling was performed to select 6 schools out of the 16 private schools and 9 schools out of the 13 public schools in the IBNW LGA. In each of the schools, systematic random sampling was performed to select the 476 satisfied teachers using the school registers as the sampling framework. All the eligible teachers who gave verbal informed consent were interviewed.

A validated questionnaire that was preliminary tested was used to obtain data for this study. A one-day training session was held for the interviewers who were research assistants to brief them on the objective of the study and on the probing techniques to be used to maintain the highest level of ethics during the research. The questionnaire included questions on socio-demographic features, single item job satisfaction questions, and general psychological health questions.

The ability of the single-item measure to pragmatically measure cognition turned it into a suitable tool in this study compared to the multidimensional instrument for assessing job satisfaction facets [8].

The single-item measure of job satisfaction was employed in this research, with teachers choosing their job satisfaction level on a 5-point Likert scale; accordingly, 1 indicated ‘very dissatisfied’, 2 indicated ‘dissatisfied’, 3 indicated ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 4 indicated ‘satisfied, and 5 indicated ‘very satisfied’. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-12 assessed psychological distress among the teachers. The GHQ-12 has already been tested in Nigeria with the sensitivity of 72%, specificity of 75%, and the Cronbach's coefficient of 0.70 [25]. In this study, two scoring methods were used, including the most commonly used GHQ-scoring approach (0-0-1-1) and the Likert scoring approach (0-1-2-3). In addition, the aggregate score for the GHQ-scoring method varied from 0-12, while that of the the Likert scoring method ranged from 0-36 [8]. This is because the GHQ 12 has 12 items or questions, and the scoring method was 0-0-1-1, implying that 0 multiplied by 12=0 for the least score and 1 multiplied by 12 = 12 for the highest score.

Although rarely used, the Likert scoring approach provides psychometric advantages by reducing data skewness and a rating approach with a cut-off point of 8/9, identifying likely cases of the psychological distress premise on the rating scale [26]. However, in the GHQ-scoring method, a threshold cut-off of 2/3 was used [27]. Besides, SPSS Statistics 25 was used to analyze the data.

The distribution of sociodemographic characteristics was reported using the frequency and percentages. The mean ± SD was reported for variables, such as age, household size, teaching experience, and overall satisfaction. In addition, a chi-squared test was used to test the association between job satisfaction and psychological distress. Besides, the relationship between job satisfaction and psychological distress was reported using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Additionally, the level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The Oyo State Ethics Committee granted ethical approval, with approval number AD13/479/4378A. A written permission was also obtained from the Oyo State Ministry of Education.

Results

A total of 476 teachers were interviewed. The respondents' age ranged from 20-67 years with the mean ± SD of 38.1 ± 9.0 years. In addition, 37.4% were in the 30-39 age group. The majority of the participants were females (55.3%), 94.1% were from the Yoruba ethnic group, and about three-quarters (76.3%) of them were married. The teachers' household size ranged from 1-13 with the mean ± SD of 4.54 ± 2.0. About two thirds of the teachers had a bachelor’s degree (64.5%), and their teaching experience ranged from 1-39 years with the mean ± SD of 10.4±7.3. In addition, the single item mean for the overall job satisfaction was 2.98 ± 1.17. In total, 307 (64.5%) respondents expressed satisfaction with their jobs. Accordingly, 251 (52.7%) were satisfied and 56 (11.8%) were relatively satisfied with their jobs. Other responses included ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’ (37, 7.8%), ‘dissatisfied’ (106, 22.3%), and ‘very dissatisfied’ (26, 5.5%).

The GHQ-12 mean score, in the case of using the Likert scoring scale, was 8.6 ± 7.6. Besides, the mean score of the GHQ-12 for the Likert scoring scale was 8.6 ± 7.6, and it was 2.4 ± 3.0 for the GHQ evaluation approach. Additionally, the GHQ rating threshold for psychological distress was 168/476 (35.3%). Furthermore, the psychological distress burden assessed by the Likert scoring cut-off was 197/476 (41.4%) (Table 1).

Job satisfaction has attracted a lot of attention in the workplace as experts believe that job satisfaction patterns can influence work efficiency, performance, participation, absenteeism, and employee retention, being an indicator of overall individual wellbeing [1]. Various academics have explained job satisfaction in various ways. In a study, job satisfaction was defined as an attitudinal variable resulting from the aggregation and balance of job likes and dislikes [2]. In addition, it was defined as any :union: of physiological, psychological, and environmental factors, leading to positive or negative job satisfaction [3].

Job satisfaction can be influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Accordingly, intrinsic factors are work-related activities primarily observed through classroom activities, such as recognition and promotion activities, whereas extrinsic factors are environmental variables, such as salaries, policies, and practices among others [4]. The importance of job satisfaction cannot be underestimated due to its major links to work performance as well as physical and mental health. This is the reason why dissatisfied teachers are more likely to be absent from work, have higher turnover intentions, and want to leave the teaching profession, thereby lowering student morale and leading to poor academic performance [5]. Furthermore, job satisfaction is directly related to work proficiency among teachers, which increases their enthusiasm for more research in educational fields and improves student academic performance [6].

Workplace success is influenced by good mental health and job satisfaction. Because of the direct relationship between job satisfaction and mental health, if teachers are emotionally fit, they will be more productive at work, leading to higher morale and a healthier lifestyle [7].

A link between work satisfaction and mental health has been established in several studies. Although previous findings indicate that psychological wellbeing is linked to job satisfaction, current findings imply that the link could be reciprocal, with mental health influencing job satisfaction as well [8].

According to research, some predictors of job satisfaction among teachers include salary, heavy workloads, insufficient cooperation among colleagues and administrators, low prestige attached to teaching, duplication of roles, lack of connections between policymakers and teachers, occupational insecurity, and career stagnation [9–12]. Studies show that teachers fall into the category of workers who cope with a variety of work-related stresses, resulting in long-term physical and mental health issues, low productivity, poor work commitment, intentions to quit, and increased burnout levels [13,14]. Similarly, epidemiological reports indicate that teachers have mental health complications at a relatively higher rate than other professions, which may be due to their work stress, pupil-related difficulties, and interpersonal disputes with colleagues [15].

However, in emerging countries like Nigeria, there are insufficient data about psychological health of teachers. Only a number of studies have reported the effect of psychological factors on job satisfaction among secondary school teachers in Nigeria using different General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) assessment instruments [16–19].

According to the literature review, job satisfaction among secondary school teachers in Nigeria ranges from 27.1 to 59.6% [17–19]. Furthermore, a similar study in Ghana found that 51% of the teachers were satisfied and 49% were dissatisfied with their job, having been higher than other studies [20]. These differences show the complexities of job satisfaction and reflect various metrics used for assessing it. The diversity observed in job satisfaction levels among teachers may have been caused by differences in the techniques utilized and cultural features of different teachers. Other studies adopted job satisfaction measures, such as the generic satisfaction scale and single item methods of assessment [17, 19].

In a study in the Benin City among teachers in private secondary schools, 17.2% of the dissatisfied teachers had psychological disorders, while 11.2% of the teachers who were satisfied had psychological disorders with a GHQ score greater than 4 [19]. Using GHQ-12, Okwaraji et al reported that 32.9% of the teachers had psychiatric morbidity in Enugu, Nigeria [17]. In contrast, using GHQ-28, Ofovwe et al reported that 20.8% of the teachers in the Egor local government of the Edo State had a score of 4 or above, which indicated the presence of psychiatric disorders [18]. These variations indicate complexities of psychological health and reflect various scales used to assess psychiatric morbidity. The use of different instruments, varied cutoffs, and sociocultural features of different individuals may contribute to the heterogeneity in psychiatric morbidity among these teachers.

Secondary education serves as a link between primary and tertiary education, being an important part of a child's formative years [21]. Job satisfaction has been recently the focus of discussion among educational psychologists due to the reduced satisfaction levels among secondary school teachers, which has been linked to the declining levels of education in Nigeria. According to some studies, secondary school graduates' intellectual capacity is not different from that of school dropouts [16, 21]. There is a low priority for treating mental health disorders in Nigeria, which has resulted in high levels of depression, anxiety, and depression among teachers; accordingly, it is supposed that teachers do not bother to seek care because of the stigmas and beliefs associated with psychological disorders in Nigeria [22, 23]. Secondary education is a very sensitive stage in both Nigeria and in many developing countries. Besides, teaching in this part of the world is considered a part-time job until better offers or higher-paying jobs become available. Thus, it is important not to neglect teachers and to ensure that their job satisfaction leads to healthy living. Although some studies have been conducted on the level of job satisfaction and the presence of psychological distress among secondary school teachers in Nigeria, few have assessed the relationship between job satisfaction and psychological disorders among secondary school teachers. This fact has resulted in a lack of data on the relationship between job satisfaction and psychological distress among secondary school teachers in southwestern Nigeria. Against this backdrop, this study aims to determine job satisfaction levels and to investigate the link between job satisfaction and psychological distress among teachers in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional research was conducted among secondary school teachers aged 18-67 years in Ibadan from July to August 2021. Ibadan is the capital of the Oyo State with 11 Local Government Areas (LGAs) located in southwestern Nigeria. In addition, it is the largest indigenous city by the geographical area and the third most populous city in Nigeria. The majority of Ibadan residents are Yoruba’s’. The choice of schools reflects the type of secondary schools in the metropolis, which include public and private secondary schools. This study included all teachers who had worked in secondary schools for at least one year, who aged from 18 to 67 years as well as full-time teachers. Teachers ill at the time of the study as well as those who refused to participate were excluded from the study.

The teachers were chosen via multistage random sampling. At stage one, northwestern Ibadan, i.e. (IBNW) LGA, was selected purposively. The IBNW LGA was chosen due to the fact that it is one of the largest LGAs in the Ibadan metropolis and part of the old Ibadan municipality of the Oyo State [24]. At stage two, simple random sampling was performed to select 6 schools out of the 16 private schools and 9 schools out of the 13 public schools in the IBNW LGA. In each of the schools, systematic random sampling was performed to select the 476 satisfied teachers using the school registers as the sampling framework. All the eligible teachers who gave verbal informed consent were interviewed.

A validated questionnaire that was preliminary tested was used to obtain data for this study. A one-day training session was held for the interviewers who were research assistants to brief them on the objective of the study and on the probing techniques to be used to maintain the highest level of ethics during the research. The questionnaire included questions on socio-demographic features, single item job satisfaction questions, and general psychological health questions.

The ability of the single-item measure to pragmatically measure cognition turned it into a suitable tool in this study compared to the multidimensional instrument for assessing job satisfaction facets [8].

The single-item measure of job satisfaction was employed in this research, with teachers choosing their job satisfaction level on a 5-point Likert scale; accordingly, 1 indicated ‘very dissatisfied’, 2 indicated ‘dissatisfied’, 3 indicated ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 4 indicated ‘satisfied, and 5 indicated ‘very satisfied’. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-12 assessed psychological distress among the teachers. The GHQ-12 has already been tested in Nigeria with the sensitivity of 72%, specificity of 75%, and the Cronbach's coefficient of 0.70 [25]. In this study, two scoring methods were used, including the most commonly used GHQ-scoring approach (0-0-1-1) and the Likert scoring approach (0-1-2-3). In addition, the aggregate score for the GHQ-scoring method varied from 0-12, while that of the the Likert scoring method ranged from 0-36 [8]. This is because the GHQ 12 has 12 items or questions, and the scoring method was 0-0-1-1, implying that 0 multiplied by 12=0 for the least score and 1 multiplied by 12 = 12 for the highest score.

Although rarely used, the Likert scoring approach provides psychometric advantages by reducing data skewness and a rating approach with a cut-off point of 8/9, identifying likely cases of the psychological distress premise on the rating scale [26]. However, in the GHQ-scoring method, a threshold cut-off of 2/3 was used [27]. Besides, SPSS Statistics 25 was used to analyze the data.

The distribution of sociodemographic characteristics was reported using the frequency and percentages. The mean ± SD was reported for variables, such as age, household size, teaching experience, and overall satisfaction. In addition, a chi-squared test was used to test the association between job satisfaction and psychological distress. Besides, the relationship between job satisfaction and psychological distress was reported using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Additionally, the level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The Oyo State Ethics Committee granted ethical approval, with approval number AD13/479/4378A. A written permission was also obtained from the Oyo State Ministry of Education.

Results

A total of 476 teachers were interviewed. The respondents' age ranged from 20-67 years with the mean ± SD of 38.1 ± 9.0 years. In addition, 37.4% were in the 30-39 age group. The majority of the participants were females (55.3%), 94.1% were from the Yoruba ethnic group, and about three-quarters (76.3%) of them were married. The teachers' household size ranged from 1-13 with the mean ± SD of 4.54 ± 2.0. About two thirds of the teachers had a bachelor’s degree (64.5%), and their teaching experience ranged from 1-39 years with the mean ± SD of 10.4±7.3. In addition, the single item mean for the overall job satisfaction was 2.98 ± 1.17. In total, 307 (64.5%) respondents expressed satisfaction with their jobs. Accordingly, 251 (52.7%) were satisfied and 56 (11.8%) were relatively satisfied with their jobs. Other responses included ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’ (37, 7.8%), ‘dissatisfied’ (106, 22.3%), and ‘very dissatisfied’ (26, 5.5%).

The GHQ-12 mean score, in the case of using the Likert scoring scale, was 8.6 ± 7.6. Besides, the mean score of the GHQ-12 for the Likert scoring scale was 8.6 ± 7.6, and it was 2.4 ± 3.0 for the GHQ evaluation approach. Additionally, the GHQ rating threshold for psychological distress was 168/476 (35.3%). Furthermore, the psychological distress burden assessed by the Likert scoring cut-off was 197/476 (41.4%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Secondary school teachers' demographic profiles in Ibadan

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| Age group | 20-29 | 94 | 19.7 |

| 30-39 | 178 | 37.4 | |

| 40-49 | 139 | 29.2 | |

| ≥50 | 65 | 13.7 | |

| Gender | Male | 213 | 44.7 |

| Female | 263 | 55.3 | |

| Religion | Christianity | 297 | 62.4 |

| Islam | 174 | 36.6 | |

| Traditional | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Others | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Marital status | Married | 363 | 76.3 |

| Single | 109 | 22.9 | |

| Widow/Widower | 4 | 0.8 | |

| Ethnicity | Yoruba | 448 | 94.1 |

| Igbo | 17 | 3.6 | |

| Hausa | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Others | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Level of education | High school diploma/NCE | 74 | 15.5 |

| Bachelor's degree | 307 | 64.5 | |

| Master's degree | 73 | 15.3 | |

| PhD | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Others | 21 | 4.4 | |

| Teaching experience | 0-5 | 148 | 31.1 |

| 6-10 | 139 | 29.2 | |

| 11-20 | 131 | 27.5 | |

| 21-30 | 54 | 11.3 | |

| >30 | 4 | 0.8 | |

| Level of income | ≤30,000 | 110 | 23.1 |

| 30,000-50,000 | 165 | 34.7 | |

| 50,000-100,000 | 152 | 31.9 | |

| >100,000 | 49 | 10.3 | |

| Mean ± SD | |||

| Age | 38.1 ± 9.0 | ||

| Household size | 4.5 ± 2.0 | ||

| Teaching experience | 10.4 ± 7.4 | ||

| Overall job satisfaction | 3.0 ± 1.2 | ||

Table 2 is the contingency table for the relationship between job satisfaction categories and psychological distress. Accordingly, a dose-response relationship was established between job satisfaction and the positive screen for psychological distress. The psychological distress burden increased gradually with less satisfaction in the dissatisfied group, showing a significantly higher proportion of the positive screen (48.5%) compared to either the satisfied group (30.0%) or the undecided group (32.4%) (Table 2). This dose response relationship was more unequivocal with the Likert scoring scale, as Table 3 shows.

Table 2. Job satisfaction and psychological distress (GHQ scores) among teachers in the selected secondary schools in Ibadan, 2021

| Satisfaction category | Psychological distress positive screen | ||

| Yes | No | Total | |

| Satisfied | 92(30%) | 215(70%) | 307 |

| Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied | 12(32.4%) | 25(67.6%) | 37 |

| Dissatisfied | 64(48.5%) | 68(51.5%) | 132 |

| Total | 168(35.3%) | 308(64.7%) | 476 |

Chi-square value = 14.00, p < 0.001

Table 3. Job satisfaction and psychological distress (the Likert scoring method) among teachers in the selected schools in Ibadan, 2021

Table 3. Job satisfaction and psychological distress (the Likert scoring method) among teachers in the selected schools in Ibadan, 2021

| Satisfaction category | Psychological distress positive screen | ||

| Yes | No | Total | |

| Satisfied | 108(35.2%) | 199(64.8%) | 307 |

| Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied | 15(40.5%) | 22(59.5%) | 37 |

| Dissatisfied | 74(56.1%) | 58(43.9%) | 132 |

| Total | 197(41.4%) | 279(58.6%) | 476 |

Chi-square value = 16.60, p < 0.001

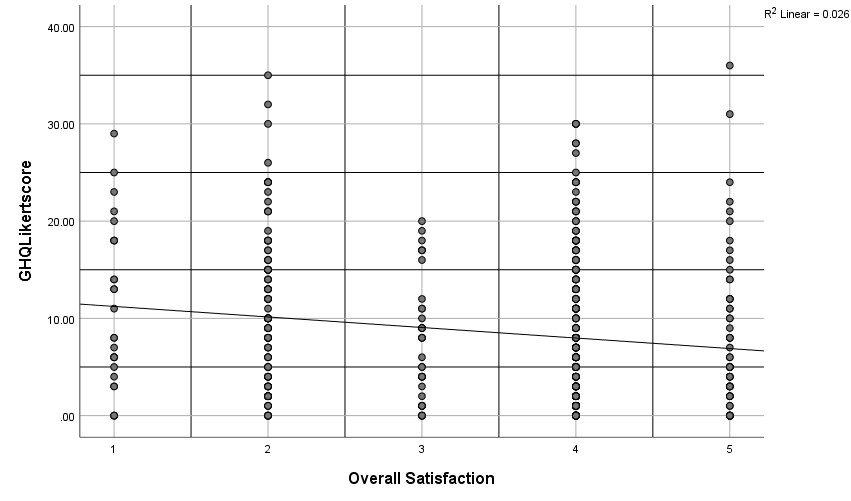

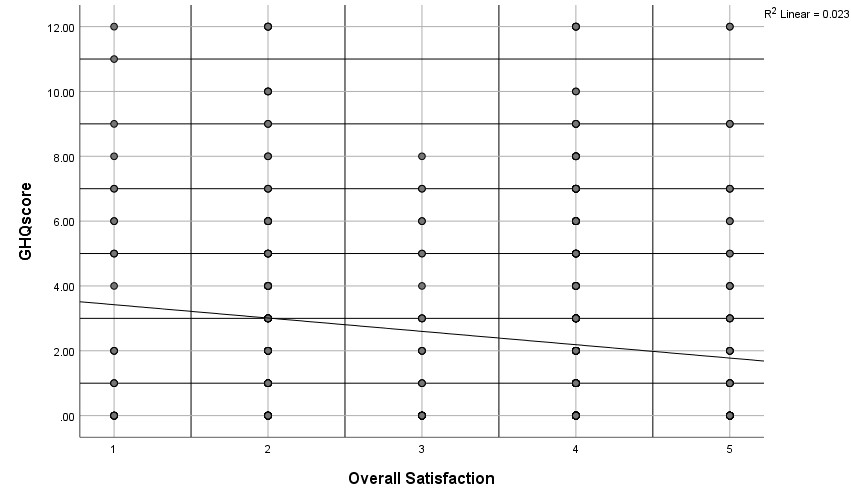

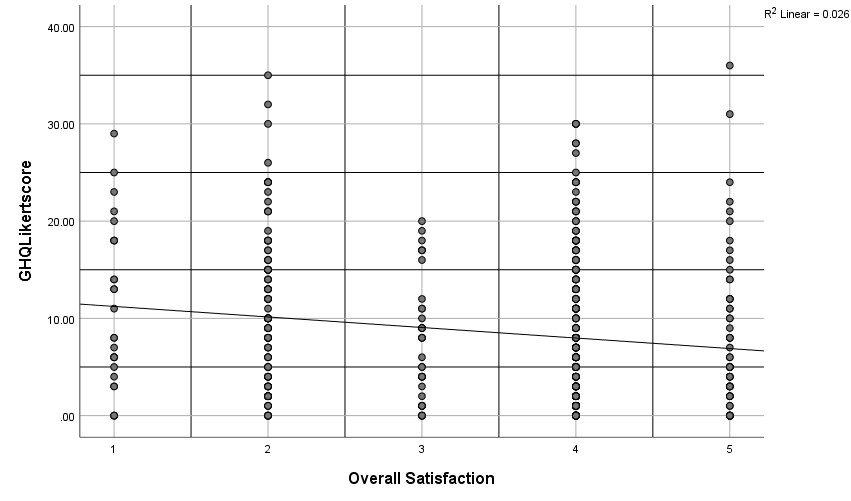

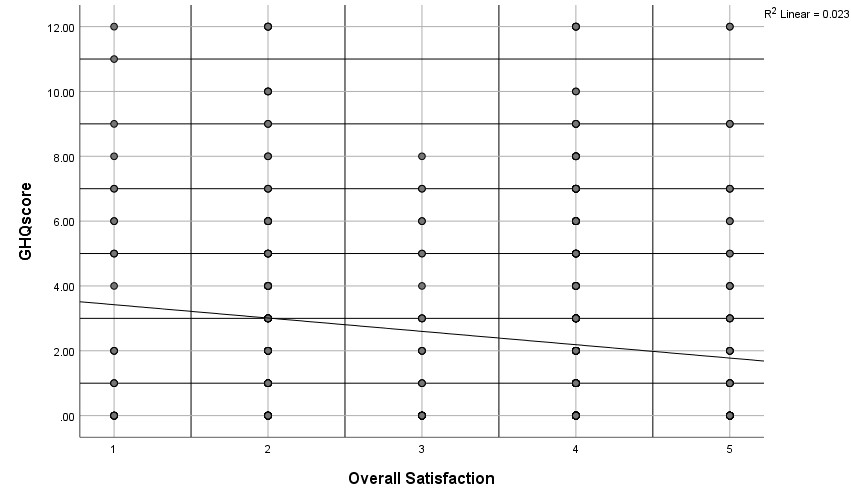

Job satisfaction values and values from both rating methods showed that the Likert rating scale (r = -0.161, p = 0.01) and the GHQ rating approach (r = -0.152, and p = 0.01) had a similar but lowly significant inverse correlation. In Figs. 1 and 2, the scatter diagram shows the relationship between satisfaction scores and GHQ scores. Accordingly, when the teachers' satisfaction values increased, GHQ-12 values decreased. In this case, r2 was about 0.023 and 0.026, indicating that the correlation between GHQ-12 scores and job satisfaction scores was about 2.3 and 2.6% of the differences in the GHQ-12 scores, respectively (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. The scatter diagram of the GHQ Likert score versus the overall job satisfaction score for present jobs among teachers in Ibadan, 2021

Job satisfaction groups: 1 indicates ‘very dissatisfied’, 2 indicates ‘dissatisfied’, 3 indicates ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 4 indicates ‘satisfied’, 5 indicates ‘very satisfied’.

Fig. 2. The scatter diagram of the GHQ Score versus the overall job satisfaction score among teachers in Ibadan, 2021

Job satisfaction Group: 1 indicates ‘very dissatisfied’, 2 indicates ‘dissatisfied’, 3 indicates ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 4 indicates ‘satisfied’, 5 indicates ‘very satisfied’.

Discussion

According to the findings of this study, two-thirds of the teachers were satisfied with their jobs, but two-fifths of them were under psychological distress. In addition, a low inverse relationship was observed between job satisfaction and psychological distress.

Teachers in Nigeria show different rates of job satisfaction, as corroborated by this research. In this study, higher psychological distress was evident than in other studies. Okwaraji et al reported an almost similar level of mild psychological distress among teachers [17]. In contrast, Ofovwe et al reported a lower level of psychological distress, than the present study, among secondary school teachers in the Enugu State, Nigeria [18]. The reason for this variation could be different geographical and cultural characteristics of the respondents. As noted in another study conducted among physicians [8], psychiatric morbidity among Nigerian workers appeared to be on the rise compared to previous reports of a decade ago. This could be associated with the worsening economic conditions in this country.

The effect of the very low rate of job satisfaction due to psychological distress among the respondents looks significant in this study, with over half of the dissatisfied teachers undergoing psychological distress. In the same vein, a low positive relationship was observed between job satisfaction and psychological wellbeing in secondary school teachers in Ankara [28]. This has a serious implication about job satisfaction among teachers, which affects the development of a country, as the school system growth is relevant to national growth. Teachers who are dissatisfied with their job are more likely to quit their job as they feel the school does not deserve their commitment, with this affecting both quality of education and student performance [29].

Job satisfaction values and GHQ values were found to have a moderate negative correlation. This implies that higher satisfaction among teachers improves psychological well-being among them. This was in line with the finding of Aliakbari et al who, in a correlational study, observed a significant connection between job satisfaction and psychological distress [1]. In the same vein, a study among secondary school teachers in eastern Nigeria found a significant association between job satisfaction and psychological distress among teachers [17]. A study in Gaza and the West Bank among teachers in the primary school and the lower secondary school reported that psychological distress had a moderate inverse relationship with the level of work engagement [30]. The difference observed could be due to the fact that only private schools were used in this study, which could have led to the lower level of satisfaction among teachers.

It is noteworthy that upon categorization of psychological distress using various scoring methods, a dose-response relationship was observed between job satisfaction and psychological distress. A shift in job satisfaction from the satisfied group to the dissatisfied group resulted in a corresponding increase in psychological distress. This further supports the claim that the high level of job satisfaction can maintain good mental health among workers, being in line with the finding of Bello et al among doctors in southern Nigeria [31].

One of the limitations of this study is that it was conducted after COVID-19 lockdowns, which might have impacted psychological distress among the teachers prior to the study. This could have influenced the status of psychological disorders compared to other studies done before the COVID-19 pandemic.

A prospective design, such as a cohort study, would be more suitable for establishing a clear relationship between job satisfaction and psychological distress; hence, this would help determine which variable is dependent on the other, because of the difficulty in establishing a causal relationship between job satisfaction and psychological distress.

Conclusion

According to the findings of this study, a low significant correlation was established between both job satisfaction and psychological distress. Furthermore, there was a significant negative linear dose-response association between job satisfaction and psychological distress. These findings would help stakeholders in the education system to provide substantial incentives for improving job satisfaction and performance in secondary school teachers. This study recommends that school management organize public health education programs and create more platforms for teachers to talk about their mental health challenges.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank all participants for their constructive and active assistance with this study.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Fig. 1. The scatter diagram of the GHQ Likert score versus the overall job satisfaction score for present jobs among teachers in Ibadan, 2021

Job satisfaction groups: 1 indicates ‘very dissatisfied’, 2 indicates ‘dissatisfied’, 3 indicates ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 4 indicates ‘satisfied’, 5 indicates ‘very satisfied’.

Fig. 2. The scatter diagram of the GHQ Score versus the overall job satisfaction score among teachers in Ibadan, 2021

Job satisfaction Group: 1 indicates ‘very dissatisfied’, 2 indicates ‘dissatisfied’, 3 indicates ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 4 indicates ‘satisfied’, 5 indicates ‘very satisfied’.

Discussion

According to the findings of this study, two-thirds of the teachers were satisfied with their jobs, but two-fifths of them were under psychological distress. In addition, a low inverse relationship was observed between job satisfaction and psychological distress.

Teachers in Nigeria show different rates of job satisfaction, as corroborated by this research. In this study, higher psychological distress was evident than in other studies. Okwaraji et al reported an almost similar level of mild psychological distress among teachers [17]. In contrast, Ofovwe et al reported a lower level of psychological distress, than the present study, among secondary school teachers in the Enugu State, Nigeria [18]. The reason for this variation could be different geographical and cultural characteristics of the respondents. As noted in another study conducted among physicians [8], psychiatric morbidity among Nigerian workers appeared to be on the rise compared to previous reports of a decade ago. This could be associated with the worsening economic conditions in this country.

The effect of the very low rate of job satisfaction due to psychological distress among the respondents looks significant in this study, with over half of the dissatisfied teachers undergoing psychological distress. In the same vein, a low positive relationship was observed between job satisfaction and psychological wellbeing in secondary school teachers in Ankara [28]. This has a serious implication about job satisfaction among teachers, which affects the development of a country, as the school system growth is relevant to national growth. Teachers who are dissatisfied with their job are more likely to quit their job as they feel the school does not deserve their commitment, with this affecting both quality of education and student performance [29].

Job satisfaction values and GHQ values were found to have a moderate negative correlation. This implies that higher satisfaction among teachers improves psychological well-being among them. This was in line with the finding of Aliakbari et al who, in a correlational study, observed a significant connection between job satisfaction and psychological distress [1]. In the same vein, a study among secondary school teachers in eastern Nigeria found a significant association between job satisfaction and psychological distress among teachers [17]. A study in Gaza and the West Bank among teachers in the primary school and the lower secondary school reported that psychological distress had a moderate inverse relationship with the level of work engagement [30]. The difference observed could be due to the fact that only private schools were used in this study, which could have led to the lower level of satisfaction among teachers.

It is noteworthy that upon categorization of psychological distress using various scoring methods, a dose-response relationship was observed between job satisfaction and psychological distress. A shift in job satisfaction from the satisfied group to the dissatisfied group resulted in a corresponding increase in psychological distress. This further supports the claim that the high level of job satisfaction can maintain good mental health among workers, being in line with the finding of Bello et al among doctors in southern Nigeria [31].

One of the limitations of this study is that it was conducted after COVID-19 lockdowns, which might have impacted psychological distress among the teachers prior to the study. This could have influenced the status of psychological disorders compared to other studies done before the COVID-19 pandemic.

A prospective design, such as a cohort study, would be more suitable for establishing a clear relationship between job satisfaction and psychological distress; hence, this would help determine which variable is dependent on the other, because of the difficulty in establishing a causal relationship between job satisfaction and psychological distress.

Conclusion

According to the findings of this study, a low significant correlation was established between both job satisfaction and psychological distress. Furthermore, there was a significant negative linear dose-response association between job satisfaction and psychological distress. These findings would help stakeholders in the education system to provide substantial incentives for improving job satisfaction and performance in secondary school teachers. This study recommends that school management organize public health education programs and create more platforms for teachers to talk about their mental health challenges.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank all participants for their constructive and active assistance with this study.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

1. Aliakbari A. The impact of job satisfaction on teachers’ mental health: A case study of the teachers of Iranian Mazandaran province. World Sci News 2015; 12:1-11. [Article]

2. Bashir L. Job Satisfaction of Teachers In Relation to Professional Commitment. Int J Indian Psychol 2017; 4(4). doi:10.25215/0404.007. [DOI]

3. Jalagat R. Job Performance, Job Satisfaction and Motivation: A Critical Review of Their Relationship. Int J Adv Manag Econ 2016; 5(6):36-43. [Article]

4. Omer Soran K. The impact of corporate social responsibility on employee’s job satisfaction. J Process Manag New Technol 2018; 6(3):56-64. [DOI]

5. Kemunto ME, Raburu PA, Joseph B. Does Age Matter? Job Satisfaction of Public Secondary School Teachers. Int J Sci Res 2018; 7(9). [Article]

6. Gopinath R. Influence of Job Satisfaction and Job Involvement of Academicians with special reference to Tamil Nadu Universities. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil 2020; 24(3):4296-306. [Article] [DOI]

7. Rinsangi LVL. Mental Health and Job Satisfaction of College Teachers. Int J Peace Educ Dev 2018; 6(1):39-46. [DOI]

8. Bello S, Afolabi RF, Adewole DA. Job Satisfaction and Psychiatric Morbidity among Resident Doctors in Selected Teaching Hospitals in Southern Nigeria: A web-based Survey. J Occu Health Epidemiol 2019; 8(4):199-206. [DOI]

9. Crisci A, Sepe E, Malafronte P. What influences teachers’ job satisfaction and how to improve, develop and reorganize the school activities associated with them. Qual Quant 2019; 53(5):2403-19. [DOI]

10. Shahi BB. Job Satisfaction and Performance of Community Secondary School Teachers in Nepal: An Exploration and Analysis. Artech J Art Soc Sci 2020; 2(4):105-14. [Article]

11. Sultana A, Sarker MNI, Prodhan SA. Job Satisfaction of Public and Private Primary School Teachers of Bogra District in Bangladesh. J Sociol Anthropol 2017; 1(1):41-6. [Article]

12. Iwu CG, Ezeuduji IO, Iwu IC, Ikebuaku K, Tengeh RK. Achieving Quality Education by Understanding Teacher Job Satisfaction Determinants. Soc Sci 2018; 7(2):25.doi:10.3390/socsci7020025 [DOI]

13. Bernotaite L, Malinauskiene V. Workplace bullying and mental health among teachers in relation to psychosocial job characteristics and burnout. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2017; 30(4):629-40. [DOI] [PMID]

14. Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S. Still motivated to teach? A study of school context variables, stress and job satisfaction among teachers in senior high school. Soc Psychol Educ 2017; 20(1):15-37. [DOI]

15. Schonfeld IS, Bianchi R, Luehring-Jones P. Consequences of Job Stress for the Mental Health of Teachers. In: Educator Stress. New York City, United States: Springer; 2017. [DOI]

16. Akomolafe J, Ogunmakin AO. Job Satisfaction among Secondary School Teachers: Emotional Intelligence, Occupational Stress and Self-Efficacy as Predictors. J Educ Soc Res 2014; 4(3):487-98. [DOI]

17. Okwaraji FE, Aguwa EN. Burnout, Psychological Distress and Job Satisfaction among Secondary School Teachers in Enugu, South East Nigeria. J Psychiatry 2015; 18(1):198. doi:10.4172/Psychiatry.1000198 [DOI]

18. Ofovwe CE, Ofili AN, Ojetu OG, Okosun FE. Marital satisfaction, job satisfaction and psychological health of secondary school teachers. Health (Irvine Calif) 2013; 5(4):663-8. [DOI]

19. Ofili AN, Usiholo EA, Oronsaye MO. Psychological morbidity, job satisfaction and intentions to quit among teachers in private secondary schools in Edo-State, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2009; 8(1):32-7. [DOI] [PMID]

20. Appiah-Agyekum NN, Suapim RH, Peprah SO. Determinants of Job Satisfaction among Ghanaian Teachers. J Educ Pract 2013; 4(3):43-50. [Article]

21. Azi DS. Enhancing Job Satisfaction for Teachers : A Strategy for Achieving Transformation of Secondary Education in Nigeria. J Educ Pract 2016; 7(13):37-41. [Article]

22. Asa F, Lasebikan VO. Mental health of teachers: teachers’ stress, anxiety and depression among secondary schools in Nigeria. Int Neuropsychiatr Dis J 2016; 7(4):1-10.

23. Okpalauwaekwe U, Mela M, Oji C. Knowledge of and Attitude to Mental Illnesses in Nigeria: A Scoping Review. Integr J Glob Health 2017; 1(1):5. [Article]

24. Onuka AOU. A comparative study of the quality of the managers, teachers and facilities of prlvate and public primary schools in Ibadan, Oyo state. Niger J Educ Adm Plan 2005; 5(2):210-6. [Article]

25. Makanjuola VA, Onyeama M, Nuhu FT, Kola L, Gureje O. Validation of short screening tools for common mental disorders in Nigerian general practices. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014; 36(3):325-9. [DOI] [PMID]

26. Ruiz FJ, García-Beltrán DM, Suárez-Falcón JC. General Health Questionnaire-12 validity in Colombia and factorial equivalence between clinical and nonclinical participants. Psychiatry Res 2017; 256:53-8. [DOI] [PMID]

27. Armino N, Gouttebarge V, Mellalieu S, Schlebusch R, van Wyk JP, Hendricks S. Anxiety and depression in athletes assessed using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) - a systematic scoping review. S Afr J Sports Med 2021; 33(1). doi: 10.17159/2078-516X/2021/v33i1a10679. [DOI]

28. Kurt N, Demirbolat AO. Investigation of the Relationship Between Psychological Capital Perception, Psychological Well-Being and Job Satisfaction of Teachers. J Educ Learn 2019; 8(1):87-99. [DOI]

29. Ajayi SO, Olatunji OA. Demographic Analysis of Turnover Intentions amongst Nigerian High School Teachers. Aust Int J Rural Educ 2017; 27(1):62-87. [Article]

30. Pepe A, Addimando L, Dagdukee J, Veronese G. Psychological distress, job satisfaction, and work engagement among Palestinian teachers: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2019; 393(S1):S40. [DOI]

31. Bello S, Adewole DA, Afolabi RF. Work Facets Predicting Overall Job Satisfaction among Resident Doctors in Selected Teaching Hospitals in Southern Nigeria: A Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Survey. J Occu Health Epidemiol 2020; 9(1):52-60. [DOI:10.29252/johe.9.1.52]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |