Volume 14, Issue 3 (Summer 2025)

J Occup Health Epidemiol 2025, 14(3): 170-177 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: 1402.185

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Fakharian E, Asgari F, Yarmohammadi S, Kalan Farmanfarma K. Predictive Factors of Aggressiveness among High School Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Occup Health Epidemiol 2025; 14 (3) :170-177

URL: http://johe.rums.ac.ir/article-1-987-en.html

URL: http://johe.rums.ac.ir/article-1-987-en.html

Related article in

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

Similar articles

1- Professor, Trauma Research Center, Dept. of Neurosurgery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

2- M.Sc. in Environmental Health Engineering, Trauma Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran

3- Assistant Prof., Trauma Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

4- Assistant Prof., Trauma Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran. ,kalan_farma@yahoo.com

2- M.Sc. in Environmental Health Engineering, Trauma Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran

3- Assistant Prof., Trauma Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

4- Assistant Prof., Trauma Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran. ,

Article history

Received: 2024/12/26

Accepted: 2025/05/5

ePublished: 2025/09/28

Accepted: 2025/05/5

ePublished: 2025/09/28

Subject:

Epidemiology

Keywords: Predictive Factors , Aggression [MeSH], Adolescents [MeSH], Schools [MeSH], Cross-Sectional Studies [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 481 kb]

(408 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (763 Views)

Table 2. Predictive factor for aggression among the students studied

Full-Text: (284 Views)

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical stage of life marked by the search for identity, significantly influencing teenage behavior. Thus, violence is frequently observed among teenagers in schools, posing a significant social issue [1]. This violence can have serious implications for the health and well-being of both schools and adolescents [2]. The World Health Organization defines adolescent violence as any action that harms health, well-being, mental coherence, freedom, and the right to full development [1]. Aggressive behaviors exhibited by adolescents can lead to significant repercussions across diverse cultures and countries [3]. Approximately 1 in 10 teenagers manifest aggressive behavior or are victims of peer violence [4]. This coincides with 200,000 homicides among this age group worldwide each year, with the majority occurring in low- and middle-income countries, and 83% of the victims being male [5, 6]. Contributing factors include excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, dysfunctional family dynamics, rejection from parents and society, unemployment, economic inequality, suicide attempts, school dropout, mental distress, emotional problems in childhood, discrimination, and low intelligence [7, 8]. Studies have indicated that students with a history of school violence are more likely to experience academic decline, social maladjustment, and negative behaviors throughout their lives [9, 10]. A study of 2,800 Iranian adolescents demonstrated a high prevalence of verbal (45%) and physical violence (33.3%). Factors such as male gender, carrying weapons, feeling unsafe at school, and experiencing family violence were identified as contributors to adolescent violence [11]. Violent behavior significantly inhibits creativity, fosters a hostile atmosphere, and causes anxiety in the academic environment [12]. Thus, ensuring security and peace in schools is essential for children and teenagers to learn and have positive growth experiences [13].

In spite of the generally constructive role of educational institutions, schools may occasionally become environments where violent behaviors could be internalized through social learning. According to social learning theory, individuals exposed to attitudes that endorse and promote law-breaking are more likely to engage in criminal behavior [1]. Early-life violence can predict behavioral disorders later in life. Violence is a relational phenomenon in which various factors interact with one another. These factors range from individual characteristics to broader social variables. Hence, the analysis of aggression in schools should capture the gradual interplay between the developmental traits of adolescents and the characteristics of their surrounding environment. Family and school constitute the closest social contexts for a developing adolescent, where the interaction between these environments and the individual traits of the adolescent is the primary focus of the analysis [14]. Since family and school are the most important social contexts for a developing teenager, the interaction between these contexts and the individual characteristics of adolescents can predict the occurrence of aggressive behaviors. Only a few adolescents find it easy to meet their parents' expectations; thus, monitoring and the proper functioning of the family as well as parents play a key role in the socialization and behavioral development of adolescents. Conversely, schools where positive interactions occur between teachers and students help foster self-guidance and tension management skills, ultimately minimizing aggression in teenagers [15].

On the other hand, in schools where there are positive interactions between teachers and students, an environment of self-guidance and tension management skills is fostered, eventually minimizing aggression among adolescents [16].

This study explores key factors contributing to teen aggression in Kashan, Iran - a region characterized by unique cultural dynamics rarely studied in psychology. It addresses three critical gaps: lack of local data on aggression triggers, how traditional parenting clashes with modern school pressures, and the need for culturally-tailored solutions. Using a socio-ecological approach, we analyze how family dynamics and school environments combine to affect aggressive behaviors. The findings will help develop: better counseling for Iran's changing education system, as well as parenting programs balancing tradition with teens' growing independence. This timely research comes as Iran's youth is confronting unprecedented stress from evolving social norms and academic demands, making it essential for creating effective prevention strategies.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional, descriptive-analytical study was undertaken on 600 students in the first and second grades of junior high school in Kashan, Isfahan province, central Iran. The participants, aged 11 to 20, included both girls and boys. The study was performed along the 2023-2024 academic year. Initially, the Department of Education in Kashan city provided a list of girls' and boys' junior high and high schools. Several schools were selected via multi-stage random sampling, with students systematically enrolled based on their student ID numbers. The purpose of the study and the participation process were explained to the students, with verbal consent obtained, while also providing assurances regarding the confidentiality of their information. The participants completed the written questionnaire anonymously and self-reported.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: participants had to be enrolled in high school, age between 11 and 20 years, and provision of informed consent to participate. Exclusion criteria included students with severe cognitive impairments, language barriers, or diagnosed psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depression). Further, those who had experienced significant psychological trauma, such as the loss of a family member, over the past six months were not included in order to minimize skewed emotional responses. Only students with regular school attendance and the capacity to comprehend the questionnaire were deemed eligible. Along the data collection process, any questionnaires with more than 10% of items missing were excluded, unless the participants were able to complete the missing sections upon request.

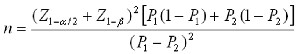

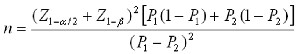

Data were collected by the researcher in schools located a peaceful setting, without using any names. Students who did not finish the questionnaire were asked to review it and answer any missing questions. Those who did not consent to answer the questions or answered more than 5% of the questionnaire incompletely were excluded from the study. The sample size, based on similar studies [11], was determined to be 600 people. This number takes into account a confidence level of 95%, a statistical power of 80%, and the possibility of excluding some samples, using the following formula.

Formula 1.

Data were collected by a standard three-part questionnaire which included demographic information, individual factors (e.g., age, gender, nationality, educational level, and interest in watching violent movies), family factors (e.g., parents' education level, occupation, family environment, number of family members, living situation, intensity of parental dependence, and parental misconduct), and social factors (e.g., alcohol consumption, drug use, specific medications, and history of school and home avoidance). The Arnold H. Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (AGQ) was also employed [17]. The questionnaire contains 29 items measuring four subscales: physical aggression (9 items), verbal aggression (5 items), anger (7 items), and hostility (8 items). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "extremely characteristic of me" to "not at all characteristic of me." Items 6 and 9, which are negatively worded, are reverse-coded. The reliability coefficient for the Persian version of the questionnaire was 0.85, reflecting high internal consistency. The total score ranges within 29- 145, with higher scores revealing higher levels of aggressiveness. Based on the study by Heizomi et al [3], a score above 80 was considered indicative of high aggression levels. The

internal consistency coefficient obtained from the factor analysis of the Persian version for all factors was over 0.70. Further, the reliability of the questionnaire was ascertained using both the test-retest method and the Cronbach's alpha coefficient, with results exceeding 0.75 for all factors [18].

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 26). Frequency and percentage indices were utilized to describe qualitative variables, whereas mean and standard deviation indices were applied to describe quantitative variables (if the distribution was normal). Independent t-tests and chi-square tests were used to explore the relationships between dependent and independent variables. Logistic regression analysis was employed to evaluate the association between independent variables and the dependent variable, adjusting for potential confounders. Variables exhibiting a p-value of lower than 0.2 in the univariate analysis were subsequently incorporated into the multivariate regression model. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 600 adolescents participated in the study, with 66% ageing 16 or older. Of the participants, 292 (48.7%) were male. Further, 457 (76.2%) were high school students, while 117 (19.5%) were of non-Iranian nationality. Most adolescents' parents had an education level below a diploma (45%). The occupations of the fathers of teenagers were primarily workers. 304 (50.7%), while the occupations of their mothers were mainly housewives. 495 (82.5%). In addition, more than 90% of the teenagers did not use alcohol, drugs, or any special medication. The relationship between the participants' characteristics and aggressiveness is reported in Table 1.

Adolescence is a critical stage of life marked by the search for identity, significantly influencing teenage behavior. Thus, violence is frequently observed among teenagers in schools, posing a significant social issue [1]. This violence can have serious implications for the health and well-being of both schools and adolescents [2]. The World Health Organization defines adolescent violence as any action that harms health, well-being, mental coherence, freedom, and the right to full development [1]. Aggressive behaviors exhibited by adolescents can lead to significant repercussions across diverse cultures and countries [3]. Approximately 1 in 10 teenagers manifest aggressive behavior or are victims of peer violence [4]. This coincides with 200,000 homicides among this age group worldwide each year, with the majority occurring in low- and middle-income countries, and 83% of the victims being male [5, 6]. Contributing factors include excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, dysfunctional family dynamics, rejection from parents and society, unemployment, economic inequality, suicide attempts, school dropout, mental distress, emotional problems in childhood, discrimination, and low intelligence [7, 8]. Studies have indicated that students with a history of school violence are more likely to experience academic decline, social maladjustment, and negative behaviors throughout their lives [9, 10]. A study of 2,800 Iranian adolescents demonstrated a high prevalence of verbal (45%) and physical violence (33.3%). Factors such as male gender, carrying weapons, feeling unsafe at school, and experiencing family violence were identified as contributors to adolescent violence [11]. Violent behavior significantly inhibits creativity, fosters a hostile atmosphere, and causes anxiety in the academic environment [12]. Thus, ensuring security and peace in schools is essential for children and teenagers to learn and have positive growth experiences [13].

In spite of the generally constructive role of educational institutions, schools may occasionally become environments where violent behaviors could be internalized through social learning. According to social learning theory, individuals exposed to attitudes that endorse and promote law-breaking are more likely to engage in criminal behavior [1]. Early-life violence can predict behavioral disorders later in life. Violence is a relational phenomenon in which various factors interact with one another. These factors range from individual characteristics to broader social variables. Hence, the analysis of aggression in schools should capture the gradual interplay between the developmental traits of adolescents and the characteristics of their surrounding environment. Family and school constitute the closest social contexts for a developing adolescent, where the interaction between these environments and the individual traits of the adolescent is the primary focus of the analysis [14]. Since family and school are the most important social contexts for a developing teenager, the interaction between these contexts and the individual characteristics of adolescents can predict the occurrence of aggressive behaviors. Only a few adolescents find it easy to meet their parents' expectations; thus, monitoring and the proper functioning of the family as well as parents play a key role in the socialization and behavioral development of adolescents. Conversely, schools where positive interactions occur between teachers and students help foster self-guidance and tension management skills, ultimately minimizing aggression in teenagers [15].

On the other hand, in schools where there are positive interactions between teachers and students, an environment of self-guidance and tension management skills is fostered, eventually minimizing aggression among adolescents [16].

This study explores key factors contributing to teen aggression in Kashan, Iran - a region characterized by unique cultural dynamics rarely studied in psychology. It addresses three critical gaps: lack of local data on aggression triggers, how traditional parenting clashes with modern school pressures, and the need for culturally-tailored solutions. Using a socio-ecological approach, we analyze how family dynamics and school environments combine to affect aggressive behaviors. The findings will help develop: better counseling for Iran's changing education system, as well as parenting programs balancing tradition with teens' growing independence. This timely research comes as Iran's youth is confronting unprecedented stress from evolving social norms and academic demands, making it essential for creating effective prevention strategies.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional, descriptive-analytical study was undertaken on 600 students in the first and second grades of junior high school in Kashan, Isfahan province, central Iran. The participants, aged 11 to 20, included both girls and boys. The study was performed along the 2023-2024 academic year. Initially, the Department of Education in Kashan city provided a list of girls' and boys' junior high and high schools. Several schools were selected via multi-stage random sampling, with students systematically enrolled based on their student ID numbers. The purpose of the study and the participation process were explained to the students, with verbal consent obtained, while also providing assurances regarding the confidentiality of their information. The participants completed the written questionnaire anonymously and self-reported.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: participants had to be enrolled in high school, age between 11 and 20 years, and provision of informed consent to participate. Exclusion criteria included students with severe cognitive impairments, language barriers, or diagnosed psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depression). Further, those who had experienced significant psychological trauma, such as the loss of a family member, over the past six months were not included in order to minimize skewed emotional responses. Only students with regular school attendance and the capacity to comprehend the questionnaire were deemed eligible. Along the data collection process, any questionnaires with more than 10% of items missing were excluded, unless the participants were able to complete the missing sections upon request.

Data were collected by the researcher in schools located a peaceful setting, without using any names. Students who did not finish the questionnaire were asked to review it and answer any missing questions. Those who did not consent to answer the questions or answered more than 5% of the questionnaire incompletely were excluded from the study. The sample size, based on similar studies [11], was determined to be 600 people. This number takes into account a confidence level of 95%, a statistical power of 80%, and the possibility of excluding some samples, using the following formula.

Formula 1.

Data were collected by a standard three-part questionnaire which included demographic information, individual factors (e.g., age, gender, nationality, educational level, and interest in watching violent movies), family factors (e.g., parents' education level, occupation, family environment, number of family members, living situation, intensity of parental dependence, and parental misconduct), and social factors (e.g., alcohol consumption, drug use, specific medications, and history of school and home avoidance). The Arnold H. Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (AGQ) was also employed [17]. The questionnaire contains 29 items measuring four subscales: physical aggression (9 items), verbal aggression (5 items), anger (7 items), and hostility (8 items). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "extremely characteristic of me" to "not at all characteristic of me." Items 6 and 9, which are negatively worded, are reverse-coded. The reliability coefficient for the Persian version of the questionnaire was 0.85, reflecting high internal consistency. The total score ranges within 29- 145, with higher scores revealing higher levels of aggressiveness. Based on the study by Heizomi et al [3], a score above 80 was considered indicative of high aggression levels. The

internal consistency coefficient obtained from the factor analysis of the Persian version for all factors was over 0.70. Further, the reliability of the questionnaire was ascertained using both the test-retest method and the Cronbach's alpha coefficient, with results exceeding 0.75 for all factors [18].

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 26). Frequency and percentage indices were utilized to describe qualitative variables, whereas mean and standard deviation indices were applied to describe quantitative variables (if the distribution was normal). Independent t-tests and chi-square tests were used to explore the relationships between dependent and independent variables. Logistic regression analysis was employed to evaluate the association between independent variables and the dependent variable, adjusting for potential confounders. Variables exhibiting a p-value of lower than 0.2 in the univariate analysis were subsequently incorporated into the multivariate regression model. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 600 adolescents participated in the study, with 66% ageing 16 or older. Of the participants, 292 (48.7%) were male. Further, 457 (76.2%) were high school students, while 117 (19.5%) were of non-Iranian nationality. Most adolescents' parents had an education level below a diploma (45%). The occupations of the fathers of teenagers were primarily workers. 304 (50.7%), while the occupations of their mothers were mainly housewives. 495 (82.5%). In addition, more than 90% of the teenagers did not use alcohol, drugs, or any special medication. The relationship between the participants' characteristics and aggressiveness is reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Relationships between characteristics of participants and aggressiveness

| Total | P-value | Non-aggressiveness N(%) | Aggressiveness N(%) | Variables | |

| 292 | 0.68 | 182(62.3) | 110(37.7) | Men | Sex |

| 308 | 187(60.7) | 121(39.3) | Female | ||

| 483 | 0.10 | 285(59.0) | 198(41.0) | Iranian | Nationality |

| 117 | 84(71.8) | 33(28.2) | Non Iranian | ||

| 457 | 0.16 | 274(60.0) | 183(40.0) | High school students | Grade |

| 143 | 95 (66.4) | 48 (33.6) | Junior high- school students | ||

| 58 | 0.01 |

39 (67.2) | 19 (32.8) | Illiterate | Mother’s education level |

| 269 | 182(67.7) | 87(32.3) | Below diploma education level | ||

| 201 | 110(54.7) | 91(45.3) | Diploma | ||

| 72 | 38(52.8) | 34(47.2) | University | ||

| 42 | 0.08 |

28(66.7) | 14(33.3) | Illiterate | Father’s education level |

| 270 | 179(66.3) | 91(33.7) | Below diploma education level | ||

| 194 | 111(57.2) | 83(42.8) | Diploma | ||

| 94 | 51(54.3) | 43(45.7) | University | ||

| 495 | 0.92 |

304(61.4) | 191(38.6) | Housewife | Mother's occupation |

| 105 | 65(61.9) | 40(38.1) | Employee | ||

| 138 | 0.08 |

86(62.3) | 52(37.7) | Employee | Father's occupation |

| 304 | 188(61.8) | 116(38.2) | Worker | ||

| 30 | 24(80.0) | 6(20.0) | Unemployed | ||

| 128 | 71(55.5) | 57(44.5) | Self-employed | ||

| 473 | <0.001 |

269(56.9) | 204(43.1) | Calm | Family space |

| 127 | 100(78.7) | 27(21.3) | Full of tension | ||

| 291 | <0.001 |

157(54.0) | 134(46.0) | Calm | Classroom space |

| 309 | 212(68.6) | 97(31.4) | Full of tension | ||

| 566 | 0.41 |

350(61.8) | 216(38.2) | Living with parents | Living situation |

| 20 | 12(60.0) | 8(40.0) | Living alone with mother | ||

| 7 | 4(57.1) | 3(42.9) | Living alone with father | ||

| 7 | 3(60.0) | 4(40.0) | Living alone with siblings | ||

| 34 | <0.001 |

30(88.2) | 4(11.8) | Yes | Alcohol use |

| 566 | 339(59.9) | 227(40.1) | No | ||

| 37 | 0.02 |

29(78.4) | 8(21.6) | Yes | Drug use |

| 563 | 340(60.4) | 223(39.6) | No | ||

| 49 | 0.56 |

32(65.3) | 17(34.7) | Yes | Taking a specific drug |

| 551 | 337(61.2) | 214(38.8) | No | ||

| 254 | 0.02 |

143(56.3) | 111(43.7) | Low | Severity of dependence on parents |

| 346 | 226(65.3) | 120(34.7) | High | ||

| 57 | <0.001 |

47(82.5) | 10(17.5) | Yes | Parental misbehavior |

| 543 | 322(58.8) | 221(41.2) | No | ||

| 298 | <0.001 |

216(72.5) | 82(27.5) | Yes | Watching violent movies |

| 302 | 153(50.7) | 149(49.3) | No | ||

| 112 | <0.001 | 93(83.0) | 19(17.0) | Yes | History of escaping from school |

| 488 | 276(56.6) | 212(43.4) | No | ||

| 52 | <0.001 | 46(88.5) | 6(11.5) | Yes | History of running away from home |

| 548 | 323(58.9) | 225(41.1) | No | ||

| 205 | 0.38 | 131(63.9) | 74(36.1) | 11-15 | Age Group |

| 395 | 238(60.3) | 157(39.7) | 16-20 | ||

| 600 | 0.10 | Means ± SD 4.69±1.32 |

Number of family members | ||

* Chi‑square test and Independent t-tests, SD: Standard deviation

Note that 231 (38.5%) students exhibited aggressive behaviors. In univariate regression analysis, the variable of aggression did not reveal a significant relationship with the father's education level : Including those who are illiterate (OR = 0.59; 95% CI: 0.27–1.26%), those with less than a diploma (OR = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.37–0.97%), and those with a diploma (OR = 0.88; 95% CI: 0.54–1.45%) compared to university education, (P=0.08), Grade (OR = 1.32; 95% CI: 0.89–1.96%) (P=0.16), or number of family members (OR = 0.89; 95% CI: 0.79–1.02%) (P=0.10). Nevertheless, other variables examined indicated a significant relationship with aggression (P<0.05). The final model demonstrated that high school students were (OR = 1.87; 95% CI: 1.20–2.84%) times more likely to be aggressive than junior high- school students, and adolescents with a high level of dependence on their parents were (OR = 1.58; 95% CI: 1.11–2.25%) times more likely to be aggressive. Adolescents in stressful classroom (OR=0.55; 95% CI: 0.38-0.79) and family environments (OR =0.35; 95% CI: 0.21-0.57) had 45% and 65% lower odds of being aggressive, respectively. Moreover, the odds of aggression were 58% lower in adolescents who were interested in watching violent movies (OR= 0.42; 95% CI: 0.29-0.60). No significant interactions were observed among the examined variables (Table 2).

Table 2. Predictive factor for aggression among the students studied

| P-value | OR (95% CI) Multivariate |

P-value | OR (95% CI) Univariate |

Variables | |

| - | - | 0.01 |

0.56 (0.36 -0.87) | Iranian | Nationality |

| 1 | Non Iranian | ||||

| 0.005 | 1.87(1.20-2.84) | 0.16 | 1.32 (0.89 -1.96) | High school | Grade |

| 1 | 1 | Junior high -school | |||

- |

- | 0.01 | 0.54(0.26-1.11) | Illiterate | Mother’s education level |

- |

0.53(0.31-0.90) | Below diploma education level | |||

| 0.92(0.53-1.58) | Diploma | ||||

| 1 | University | ||||

| - | - | 0.08 | 0.59(0.27-1.26) | Illiterate | Father’s education level |

| 0.60(0.37-0.97) | Below diploma education level | ||||

| 0.88(0.54-1.45) | Diploma | ||||

| 1 | University | ||||

| <0.001 | 0.35(0.21-0.57) | <0.001 |

0.35(0.22-0.56) | Full of tension | Family space |

| 1 | 1 | Calm | |||

| 0.001 | 0.55(0.38-0.79) | <0.001 | 0.53(0.38-0.74) | Full of tension | Classroom space |

| 1 | 1 | Calm | |||

- |

- | 0.003 | 5.02(1.74-14.44) | Yes | Alcohol use |

| 1 | No | ||||

- |

- | 0.02 | 2.37(1.06 -5.29) | Yes | Drug use |

| 1 | No | ||||

| 0.01 | 1.58(1.11-2.25) | 0.02 | 1.46(1.04 -2.03) | High | Severity of dependence on parents |

| 1 | 1 | Low | |||

| - | - | <0.001 | 3.22(1.59-6.52) | Yes | Parental misbehavior |

| 1 | No | ||||

| <0.001 | 0.42(0.29-0.60) | <0.001 | 2.56(1.82-3.60) | Yes | Watching violent movies |

| 1 | 1 | No | |||

- |

- |

<0.001 | 3.76(2.22-6.35) | Yes | History of escaping from school |

| 1 | No | ||||

| - | <0.001 | 5.34(2.24-12.71) | Yes | History of running away from home | |

| - | 1 | No | |||

| - | - | 0.10 | 0.89(0.79-1.02) | Number of family members | |

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the factors that would predict aggression among adolescents. The results revealed that high school students were approximately twice more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior compared to junior high school students. Further, adolescents with a high level of dependence on their parents indicated a greater propensity for aggression. Conversely, those adolescents experiencing stressful classroom and family environments demonstrated lower odds of engaging in aggressive behavior. Finally, adolescents who expressed an interest in watching violent movies were found to have lower odds of aggression.

According to the results, the school and family environments can serve as protective factors against aggression. The family environment, in particular, plays a key role in ameliorating adolescents' mental well-being and fostering a calm personality, especially in girls [3].

When families do not assist youngsters in adjusting to their environment, they lose an effective agent of socialization, resulting in increased stress and anxiety among family members, particularly adolescents. Along adolescence, developing independence from the family and adapting to various social and environmental demands is crucial, as young people need to learn to navigate everyday challenges related to social relationships, educational success, and employment [19].

Different family-related risk factors, such as parental marital status, family structure, parent-child relationships, substance abuse, and mental disorders, contribute to violent behavior among school children. Adolescents who witness domestic violence are more likely to manifest aggression towards others in school and other settings [15, 20]. Many adolescents whose parents punish them through shouting, slapping, or hitting often resort to aggression as a means of coping with problems (19). Conversely, a supportive educational environment at school can alleviate problematic behaviors among students. A positive school environment offers students a sense of security and opportunities for self-expression [21]. Cultural norms and school environment heavily influence adolescent aggression, as traditional attitudes and institutional practices may either mitigate or reinforce violent behaviors among students [22].

Nevertheless, schools, often perceived as safe environments, can perpetuate violence witnessed in other areas of society if such behaviors are present within them. The findings of the current study differ from those of previous research [3], which may be attributed to the smaller sample size and the specific population studied. Interestingly, this study reported that watching violent movies was associated with a diminished likelihood of aggression among adolescents. Previous research has shown a direct relationship between watching violent movies and aggressive behaviors [23, 24]; however, this is not in line with the results of the present study. While some studies have found no link between watching violent movies and a inclination towards violent behavior, others have observed that watching violent movies was associated with a decrease in violent behaviors [25, 26]. These results align with the findings of the current research. It can be stated that that not all viewers of violent films are affected similarly by what they observe. The impact of media violence on individuals is affected by factors such as attention level, aggressive tendencies, the form and content of the scene, and potentially other determining factors [25].

Conversely, robust social support networks including peers, family members, and educators—can act as a buffer against the adverse effects of media violence. Further, individuals with higher emotional intelligence (EI) tend to manifest greater resilience to aggressive stimuli, [27, 28] which could collectively explain the findings of the present study.

The study also indicated that high school students in their later years exhibited 87% more aggression compared to those in earlier years. This may be owing to lower parental supervision of older teenagers and their decreased interest in education, upbringing, and recreational activities. Hence, older teenagers rely more on their peers, resulting in peer influence and the adoption of shared beliefs, which can contribute to the development and escalation of aggressive behaviors [23]. This helps somewhat explain the aggression observed in this group of adolescents in the current study.

Furthermore, the study found that a higher level of dependence on parents was linked to a higher odd of aggression. The quality of the parent-child relationship directly influences aggression levels during adolescence; the closer adolescents are to their parents, the less likely they are to manifest aggression [29]. Nevertheless, parental psychological control may raise the likelihood of adolescents forming bonds with delinquent peers, resulting in higher aggressive behavior [30]. Adolescents who are highly dependent on their parents often comply with their demands without hesitation and strive to avoid disappointing them. Their aggressive behavior may be a way of asserting autonomy [31]. Nevertheless, this strong dependence on parents can result in diminished self-esteem, which, in turn, may promote aggression [32].

In some families, relationships are characterized by emotional fusion, where individual boundaries blur and members' thoughts, feelings, and actions become deeply intertwined. This intense emotional connection results in the unconscious transmission of feelings inside the family system, creating repetitive patterns of reaction. Those with low differentiation struggle to separate emotions from rational thought, often relying on others to shape their identity. They may hold others responsible for their happiness and make decisions primarily to relieve their own anxiety or that of those around them. Bowen (1978) refers to this state as the "false self” a persona driven by the need for approval and short-term tension mitigation rather than authentic values. In contrast, those with high differentiation possess a "solid self", grounded in clear beliefs and life principles. They balance emotional and intellectual functioning, acknowledge their dependencies, yet act autonomously while respecting others' independence. Bowen attributes these analytical capacities to the evolution of the frontal cortex in humans [33].

Perhaps to some extent, the rise in aggressive behavior in teenagers can be explained by their dependence on parents.

The differences in results between this study and others may be owing to the small sample size. Further, other factors influencing aggression, such as psychological disorders in adolescents, should be considered. A limitation of this research was the reliability and validity of participants' responses given the nature of self-reporting. Future studies should gather data from multiple sources, including teachers, parents, and peers. It should also be noted that this study utilized a cross-sectional design, so conclusions should be drawn with caution. A longitudinal study is needed to clarify causal relationships between variables.

Since the present study was performed in only one county, it is advisable for future research to be undertaken in several provinces of the country that cover a variety of ethnicities and cultures to determine the influence of cultural differences on the emergence of aggression.

The study's key strengths included its identification of critical factors influencing aggression, particularly parental attachment dynamics and environmental stressors. The unexpected inverse association between violent film exposure and aggressive behavior offers particularly valuable insights for future investigation. Further, the practical implications such as implementing developmentally-appropriate educational programs and reinforcing adolescent autonomy provide actionable guidance for policymakers as well as educators designing violence prevention interventions.

Conclusion

This study unveiled a paradoxical relationship between environmental exposures and adolescent aggression. Contrary to expectations, high parental dependency positively correlates with higher aggression, while controlled exposure to challenging familial/academic environments and violent media are inversely associated with aggressive tendencies. These findings suggest that structured stressors may offer protective benefits, while excessive parental reliance emerges as a risk factor. Interventions should adopt a developmentally sensitive framework, balancing autonomy promotion with tiered support. In this regard, a multi-systemic approach is recommended, including: school-based curricula enhancing self-efficacy and emotional regulation, family psychoeducation on stress reappraisal, and critical media engagement training. Further, graduated stressor exposure within supportive contexts may further mitigate aggression by promoting adaptive coping. The proposed intervention integrates environmental, cognitive, and relational mediators, offering a comprehensive aggression mitigation strategy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all individuals who participated in this study. We also appreciate the education and training organization, personnel, and managers of the participating high schools for their contribution to the data gathering

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, all individuals provided written informed consent. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and the anonymity of their identities throughout data analysis. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without any consequences.

Code of Ethics

The Ethics Review Board of Kashan University of Medical Sciences, approved the present study with the following number: IR.KAUMS.MEDNT.REC.1402.185

Authors' Contributions

Esmaeil Fakharian: Conception and design; Faezeh Asgari Tarazoj: Drafting the article; Soudabeh Yarmohammadi: Drafting the article; Khadijeh Kalan Farmanfarma: Collection of Data, Drafting the article, Revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the version for publication.

This study aimed to identify the factors that would predict aggression among adolescents. The results revealed that high school students were approximately twice more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior compared to junior high school students. Further, adolescents with a high level of dependence on their parents indicated a greater propensity for aggression. Conversely, those adolescents experiencing stressful classroom and family environments demonstrated lower odds of engaging in aggressive behavior. Finally, adolescents who expressed an interest in watching violent movies were found to have lower odds of aggression.

According to the results, the school and family environments can serve as protective factors against aggression. The family environment, in particular, plays a key role in ameliorating adolescents' mental well-being and fostering a calm personality, especially in girls [3].

When families do not assist youngsters in adjusting to their environment, they lose an effective agent of socialization, resulting in increased stress and anxiety among family members, particularly adolescents. Along adolescence, developing independence from the family and adapting to various social and environmental demands is crucial, as young people need to learn to navigate everyday challenges related to social relationships, educational success, and employment [19].

Different family-related risk factors, such as parental marital status, family structure, parent-child relationships, substance abuse, and mental disorders, contribute to violent behavior among school children. Adolescents who witness domestic violence are more likely to manifest aggression towards others in school and other settings [15, 20]. Many adolescents whose parents punish them through shouting, slapping, or hitting often resort to aggression as a means of coping with problems (19). Conversely, a supportive educational environment at school can alleviate problematic behaviors among students. A positive school environment offers students a sense of security and opportunities for self-expression [21]. Cultural norms and school environment heavily influence adolescent aggression, as traditional attitudes and institutional practices may either mitigate or reinforce violent behaviors among students [22].

Nevertheless, schools, often perceived as safe environments, can perpetuate violence witnessed in other areas of society if such behaviors are present within them. The findings of the current study differ from those of previous research [3], which may be attributed to the smaller sample size and the specific population studied. Interestingly, this study reported that watching violent movies was associated with a diminished likelihood of aggression among adolescents. Previous research has shown a direct relationship between watching violent movies and aggressive behaviors [23, 24]; however, this is not in line with the results of the present study. While some studies have found no link between watching violent movies and a inclination towards violent behavior, others have observed that watching violent movies was associated with a decrease in violent behaviors [25, 26]. These results align with the findings of the current research. It can be stated that that not all viewers of violent films are affected similarly by what they observe. The impact of media violence on individuals is affected by factors such as attention level, aggressive tendencies, the form and content of the scene, and potentially other determining factors [25].

Conversely, robust social support networks including peers, family members, and educators—can act as a buffer against the adverse effects of media violence. Further, individuals with higher emotional intelligence (EI) tend to manifest greater resilience to aggressive stimuli, [27, 28] which could collectively explain the findings of the present study.

The study also indicated that high school students in their later years exhibited 87% more aggression compared to those in earlier years. This may be owing to lower parental supervision of older teenagers and their decreased interest in education, upbringing, and recreational activities. Hence, older teenagers rely more on their peers, resulting in peer influence and the adoption of shared beliefs, which can contribute to the development and escalation of aggressive behaviors [23]. This helps somewhat explain the aggression observed in this group of adolescents in the current study.

Furthermore, the study found that a higher level of dependence on parents was linked to a higher odd of aggression. The quality of the parent-child relationship directly influences aggression levels during adolescence; the closer adolescents are to their parents, the less likely they are to manifest aggression [29]. Nevertheless, parental psychological control may raise the likelihood of adolescents forming bonds with delinquent peers, resulting in higher aggressive behavior [30]. Adolescents who are highly dependent on their parents often comply with their demands without hesitation and strive to avoid disappointing them. Their aggressive behavior may be a way of asserting autonomy [31]. Nevertheless, this strong dependence on parents can result in diminished self-esteem, which, in turn, may promote aggression [32].

In some families, relationships are characterized by emotional fusion, where individual boundaries blur and members' thoughts, feelings, and actions become deeply intertwined. This intense emotional connection results in the unconscious transmission of feelings inside the family system, creating repetitive patterns of reaction. Those with low differentiation struggle to separate emotions from rational thought, often relying on others to shape their identity. They may hold others responsible for their happiness and make decisions primarily to relieve their own anxiety or that of those around them. Bowen (1978) refers to this state as the "false self” a persona driven by the need for approval and short-term tension mitigation rather than authentic values. In contrast, those with high differentiation possess a "solid self", grounded in clear beliefs and life principles. They balance emotional and intellectual functioning, acknowledge their dependencies, yet act autonomously while respecting others' independence. Bowen attributes these analytical capacities to the evolution of the frontal cortex in humans [33].

Perhaps to some extent, the rise in aggressive behavior in teenagers can be explained by their dependence on parents.

The differences in results between this study and others may be owing to the small sample size. Further, other factors influencing aggression, such as psychological disorders in adolescents, should be considered. A limitation of this research was the reliability and validity of participants' responses given the nature of self-reporting. Future studies should gather data from multiple sources, including teachers, parents, and peers. It should also be noted that this study utilized a cross-sectional design, so conclusions should be drawn with caution. A longitudinal study is needed to clarify causal relationships between variables.

Since the present study was performed in only one county, it is advisable for future research to be undertaken in several provinces of the country that cover a variety of ethnicities and cultures to determine the influence of cultural differences on the emergence of aggression.

The study's key strengths included its identification of critical factors influencing aggression, particularly parental attachment dynamics and environmental stressors. The unexpected inverse association between violent film exposure and aggressive behavior offers particularly valuable insights for future investigation. Further, the practical implications such as implementing developmentally-appropriate educational programs and reinforcing adolescent autonomy provide actionable guidance for policymakers as well as educators designing violence prevention interventions.

Conclusion

This study unveiled a paradoxical relationship between environmental exposures and adolescent aggression. Contrary to expectations, high parental dependency positively correlates with higher aggression, while controlled exposure to challenging familial/academic environments and violent media are inversely associated with aggressive tendencies. These findings suggest that structured stressors may offer protective benefits, while excessive parental reliance emerges as a risk factor. Interventions should adopt a developmentally sensitive framework, balancing autonomy promotion with tiered support. In this regard, a multi-systemic approach is recommended, including: school-based curricula enhancing self-efficacy and emotional regulation, family psychoeducation on stress reappraisal, and critical media engagement training. Further, graduated stressor exposure within supportive contexts may further mitigate aggression by promoting adaptive coping. The proposed intervention integrates environmental, cognitive, and relational mediators, offering a comprehensive aggression mitigation strategy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all individuals who participated in this study. We also appreciate the education and training organization, personnel, and managers of the participating high schools for their contribution to the data gathering

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, all individuals provided written informed consent. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and the anonymity of their identities throughout data analysis. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without any consequences.

Code of Ethics

The Ethics Review Board of Kashan University of Medical Sciences, approved the present study with the following number: IR.KAUMS.MEDNT.REC.1402.185

Authors' Contributions

Esmaeil Fakharian: Conception and design; Faezeh Asgari Tarazoj: Drafting the article; Soudabeh Yarmohammadi: Drafting the article; Khadijeh Kalan Farmanfarma: Collection of Data, Drafting the article, Revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the version for publication.

References

1. Solimannejad T, Ebrahimi M, Solimannejad M. Exploring the factors affecting violence among Iranian male adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2228. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Crespo-Ramos S, Romero-Abrio A, Martínez-Ferrer B, Musitu Ochoa G. Variables psicosociales y violencia escolar en la adolescencia. Psychosoc Interv. 2017;26(2):125-30. [DOI]

3. Heizomi H, Jafarabadi MA, Kouzekanani K, Matlabi H, Bayrami M, Chattu VK, et al. Factors affecting aggressiveness among young teenage girls: A structural equation modeling approach. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2021;11(4):1350-61. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

4. Abu Al Rub M. An Assessment of Bullying/Victimization Behaviors among Third-Graders in Jordanian Public Schools. Int J Res Educ. 2018;42(3):337-67.

5. Geremew AB, Gelagay AA, Bisetegn TA, Habitu YA, Abebe SM, Birru EM, et al. Prevalence of violence and associated factors among youth in Northwest Ethiopia: Community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0264687. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

6. Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, Mokdad AA, El Bcheraoui C, Moradi-Lakeh M, et al. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people's health during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2383-401. [DOI] [PMID]

7. Obradovic-Tomasevic B, Santric-Milicevic M, Vasic V, Vukovic D, Sipetic-Grujicic S, Bjegovic-Mikanovic V, et al. Prevalence and predictors of violence victimization and violent behavior among youths: a population-based study in Serbia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17):3203. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Aboagye RG, Seidu AA, Arthur-Holmes F, Frimpong JB, Hagan Jr JE, Amu H, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with interpersonal violence among in-school adolescents in Ghana: Analysis of the global school-based health survey data. Adolescents. 2021;1(2):186-98. [DOI]

9. Estévez E, Jiménez TI, Moreno D. Aggressive behavior in adolescence as a predictor of personal, family, and school adjustment problems. Psicothema. 2018;30(1):66-73. [DOI] [PMID]

10. Jenkins LN, Demaray MK, Tennant J, Holt M. Social, emotional, and cognitive factors associated with bullying. Sch Psychol Rev. 2017;46(1):42-64. [DOI]

11. Golshiri P, Farajzadegan Z, Tavakoli A, Heidari K. Youth violence and related risk factors: A cross-sectional study in 2800 adolescents. Adv Biomed Res. 2018;7:138. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Seed S, Adhami A, Kazemipoor S. The Role of Social Behaviors and Consequences of Violence: A Qualitative Study with a Grounded Theory Approach. J Res Behav Sci. 2021;19(2):204-11. [DOI]

13. Mayer MJ, Nickerson AB, Jimerson SR. Preventing school violence and promoting school safety: Contemporary scholarship advancing science, practice, and policy. Sch Psych Rev. 2021;50(2-3):131-42. [DOI]

14. Jiménez TI, Estévez E. School aggression in adolescence: Examining the role of individual, family and school variables. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2017;17(3):251-60. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

15. El-Nady MT. Effect of family relations and school environment on aggressive behavior of school age students. Egypt J Health Care. 2021;12(2):981-97. [DOI]

16. Thomas DE, Bierman KL, Powers CJ, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. The influence of classroom aggression and classroom climate on aggressive–disruptive behavior. Child Dev. 2011;82(3):751-7. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

17. Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63(3):452-9. [DOI] [PMID]

18. Daneshpour A, Sarvghad S. The relationship between metacognitive strategies with aggression and coping Styles in Shiraz High School Students. Psychological Methods and Models. 2010;1(2):75-92. [URL]

19. Sharma D, Sangwan S. Impact of family environment on adolescents aggression. Adv Res J Soc Sci. 2016;7(2):225-9. [DOI]

20. Yarmohammadi S, Ghaffari M, Yarmohammadi H, Hosseini Koukamari P, Ramezankhani A. Relationship between quality of life and body image perception in Iranian medical students: structural equation modeling. Int J Prev Med. 2020;11:159. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

21. Li Z, Yu C, Nie Y. The association between school climate and aggression: a moderated mediation model. Int J Environ Rese Public Health. 2021;18(16):8709. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

22. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; Committee on Law and Justice; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Board on Global Health; et al. Addressing the Social and Cultural Norms That Underlie the Acceptance of Violence Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018. [DOI] [PMID] [Bookshelf ID]

23. Hojati M, Abasi M, Ghadampour E. Modeling of aggression in School Based on Family Functioning, Neuroticism, School climate: The Mediating Role of Belief to Aggression, Empathy, and School Attachment. Soc Psychol Res. 2022;12(47):77-98.

24. Rostad WL, Basile KC, Clayton HB. Association among television and computer/video game use, victimization, and suicide risk among US high school students. J interpers violence. 2021;36(5-6):2282-305. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

25. Golshiri P, Farajzadegan Z, Mirzaean M, Motamedi N. The Relationship Between Movie Violence and Violent Behavior in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study in Isfahan, Iran. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2023;17(3):e116383. [DOI]

26. Dahl G, DellaVigna S. Does movie violence increase violent crime? Q J Econ. 2009;124(2):677-734. [DOI]

27. Ferguson CJ. Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(5):646-66. [DOI] [PMID]

28. Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G. Emotional intelligence as a standard intelligence. Emotion.2001;1(3):232-42. [DOI] [PMID]

29. Lakhdir MPA, Rozi S, Peerwani G, Nathwan AA. Effect of parent-child relationship on physical aggression among adolescents: Global school-based student health survey. Health Psychol Open. 2020;7(2):2055102920954715. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

30. Tian Y, Yu C, Lin S, Lu J, Liu Y, Zhang W. Parental psychological control and adolescent aggressive behavior: Deviant peer affiliation as a mediator and school connectedness as a moderator. Front psychol. 2019;10:358. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

31. Estévez E, Góngora JN. Adolescent aggression towards parents: Factors associated and intervention proposals. In: Quin C, Tawse S, editors. Handbook of aggressive behavior research. Hauppauge, New York, United States. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2009:143-64.

32. Muarifah A, Mashar R, Hashim IHM, Rofiah NH, Oktaviani F. Aggression in adolescents: the role of mother-child attachment and self-esteem. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022;12(5):147. [DOI] [PMID] [PMCID]

33. Kolbert JB, Crothers LM, Field JE. Clinical interventions with adolescents using a family systems approach. Fam J. 2012;21(1):87-94. [DOI]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |